- Details

- By Tommy Orange

Editor’s Note: This commentary first appeared in the Los Angeles Times on November 23, 2017. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

The first Thanksgiving I remember, I was in the second grade. I didn’t know my teacher had asked my dad to come talk to the class. When he walked in, I was embarrassed to see him there. He said that white people came and didn’t know how to survive on this land, so we helped them out, then celebrated with a meal. It was a story I’d heard in school before, but not at home.

At home, we heard the story of the Sand Creek Massacre — about how our Cheyenne relatives made it through, in November 1864. We were told to fly the American flag. We flew a white one too. And we were gathered around those flags, on our knees begging for mercy, when they came for us.

My dad was born and raised on a reservation in Oklahoma. He didn’t speak English, or even see a white person, until he was 5 years old. I grew up in Oakland. My mom is white, and we lived near her side of the family. I hardly ever saw other Native people.

I’m embarrassed now that I was embarrassed then. I feel shame that I felt shame to see my father — there to tell us a story about Thanksgiving. My heritage had felt invisible my whole life. It didn’t feel right to be seen, all of a sudden.

Last year, we got national media attention at the Dakota Access Pipeline protests when they sicced their dogs on us. The last time we got that kind of attention, Richard Nixon was in office, when we occupied Alcatraz for almost two years. That occupation started the week of Thanksgiving 1969. In North Dakota almost 50 years later, private militia spent the week of Thanksgiving shooting Native protesters with rubber bullets and spraying us with freezing water. Some of us had never seen ourselves onscreen. And then we saw them trying to get rid of us like time never moved, like the Indian wars didn’t end, just went cold.

At Sand Creek, Col. John Chivington said, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians.” He and his men killed more than 200 elders, women and children in one day. Chivington was never held accountable for his actions. Damn sympathy, crude oil flows freely under Native land in North Dakota today.

I grew up celebrating the Thanksgiving holiday the same as everyone else. I’m ashamed that I haven’t thought more critically about the day — ashamed at my inherent complicity in celebrating that single meal.

There was one meal in 1621. In 1622, the Indian Wars began. Native people were systematically erased through genocidal policy. The Indian Wars ended in 1924. But again, they just went cold because as soon as they ended, the Indian termination era began. Those battles were won by passing legislation that made it harder for us to stay visible, to thrive as a people, to stay alive.

This November, most Americans will sit down with their families and eat a Thanksgiving meal. Some still will be recovering from the night before, which is now known as Blackout Wednesday — the most profitable night of the year in bars across the country. Others will have their children tell the story about the Indians and the Pilgrims. And plenty of people will feel genuine gratitude. Most won’t think about the history of the meal before, during or after digesting their turkey.

We can see the eye roll coming before we explain the reason why the holiday is complicated for us. We’ve explained before to the same eyes that only want to look away, not have to get political. To those of us who suffer from history’s consequences and don’t benefit from them, talking about our beliefs, even just telling our stories, is automatically political.

We — you and I and everyone — are still trying to absolve ourselves of history. But we don’t want to do it by talking about it. We don’t want the taste of it in our mouths. We’re devoted to keeping it under our place mats. Blackout Wednesday. Gorge Thursday. Get deals Friday. We hide the lie under the darkness of digestion.

One this is: We don't have to buy turkey, we don't have to buy int any of it. Sure, it's a tradition, so is the Confederate flag.

Here’s what we can all do this Thanksgiving: Anything else. Everyone has the day off. Most people have an unchecked investment in the holiday. They might not say it, but they want to keep the illusion that America’s roots are true.

On Tuesday, the president pardoned a turkey. You should know that turkeys who are pardoned by presidents go up to a farm in Virginia where they usually die within a month. They’re bred for the table. There are zero surviving past-pardoned turkeys.

Celebrate the holiday, or don’t. Believe in American mercy, or don’t. But look where tradition has gotten us so far. Look where we are now.

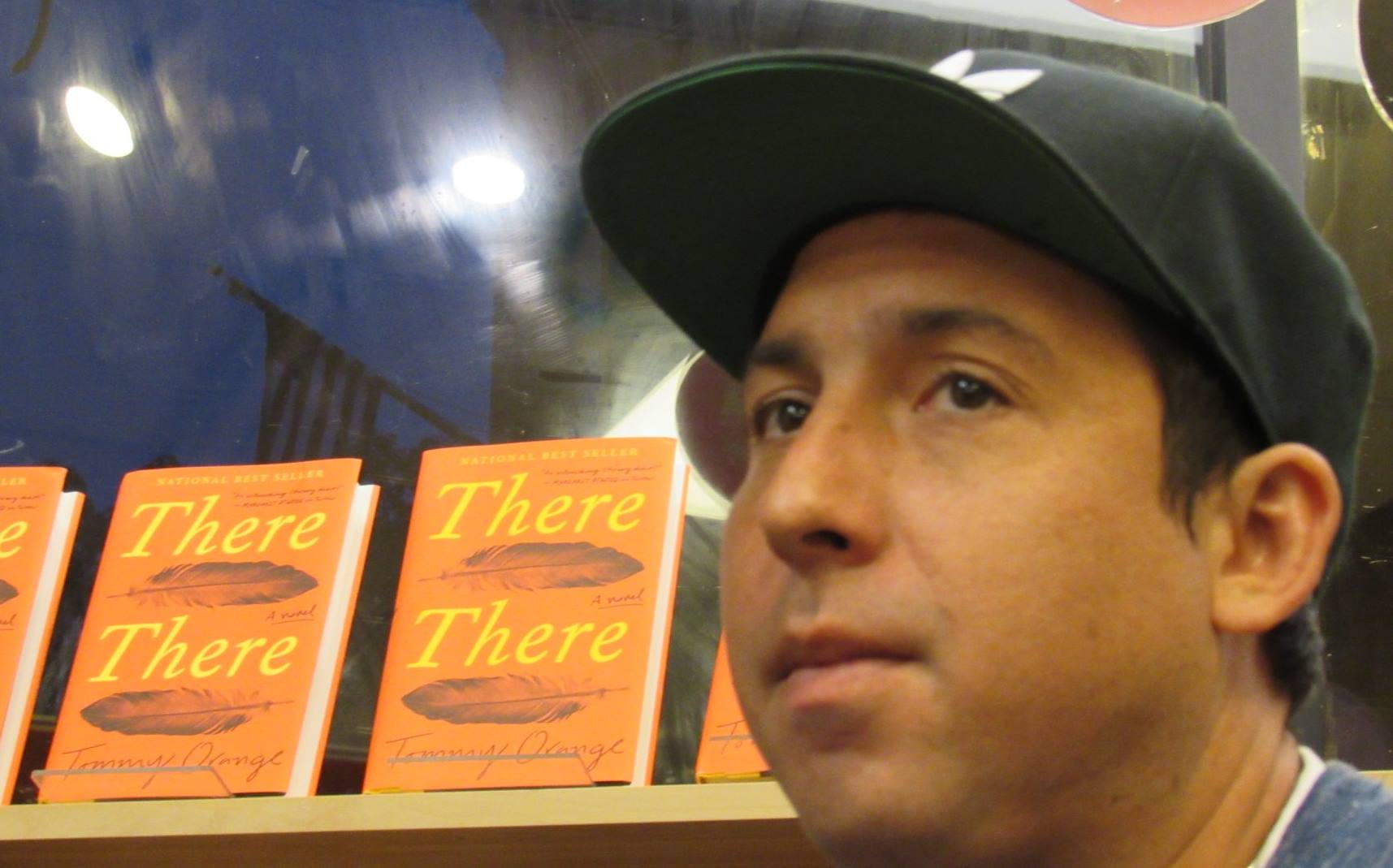

Tommy Orange is tribal citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. He teaches at the MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts. His best-selling novel “There There” was published earlier in 2018. He is a 2014 MacDowell Fellow, and a 2016 Writing by Writers Fellow. He was born and raised in Oakland, California, and currently lives in Angels Camp, California.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher