Lifelong cemetery caretaker Bob Sam (left) and his daughter Birdie Sam (right) at a March 9 ceremony to honor the souls of hundreds of Alaska Native people who died at a government-funded asylum throughout the 1900s. Sam, who is ill, shared that this will be his final repatriation project after 40 years of returning ancestors.

MOURNING MORNINGSIDE

Alaska Native Souls Honored and Freed from Oregon Asylum Graveyards

Story and photography by Jenna Kunze

PORTLAND, Ore.—The souls of more than 300 Alaska Native people who died throughout the 20th century at a psychiatric hospital more than 1,700 miles from their homes were released on their journey into the afterlife this month.

Alaska Native relatives and allies, seated around a circle in an all-day ceremony on March 9, donned regalia, prayed, sang songs, shared stories, and danced in honor of their ancestors who never came home.

Tlingit elder Bob Sam, 70, a lifelong repatriation expert and cemetery caretaker in Alaska, led the ceremony. Behind him stood a table full of children’s toys: teddy bears, marbles, and games were offered up as gifts for the young departed souls.

“In Alaska, as living people, we suffer racism, prejudice, hatred,” Sam told the attendees. “But many people don't know that our dead suffer more. Our dead are neglected and forgotten people.”

From the early 1800s through the 1960s, federal policy supported the mass removal of hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children from their homes. Natives were sent to Indian boarding schools throughout the country for the dual purpose of cultural assimilation and land dispossession, according to the 2022 investigative report on the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. An estimated tens of thousands died at these schools, and were buried away from their homes, families, and communities.

But it wasn’t just Indian boarding schools the government used to carry out its federal policy. During the same time period, the Department of the Interior also operated or paid for 1,000 sanitariums, insane asylums, orphanages and other facilities that housed or “treated” Native American and Alaska Native people, according to the federal investigation—institutions of different names disguising the same goal.

For more than six decades — starting in 1904 and ending in 1968 — Alaska lacked institutions to care for those with physical and mental disabilities, and mental illness was considered a crime. As a result, Alaskan adults and children who were tried and convicted of being “really and truly insane” by a six-person jury of white men were sent by the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) for treatment at a private asylum in Portland: Morningside Hospital.

In total, close to 5,000 Alaskans were committed to Morningside, for diagnoses including: suicidal tendencies, head injuries, drug abuse, epilepsy, dementia, postpartum depression, alcoholism, birth defects, syphilis, and imbecility, according to court records gathered across the state and country by a group of volunteer researchers.

Many were never heard from by their families again. Death certificates show that more than 1,100 Alaskans died at Morningside. Hundreds of them were Indigenous.

Nearly a century later, Alaska Native families and tribes are slowly beginning to trace their collective history back to Morningside. One tribe in Southeast Alaska, Ketchikan Indian Community, is investigating a connection between the time certain ancestors were committed to Morningside with the time deeds show land transfer to non-Native hands.

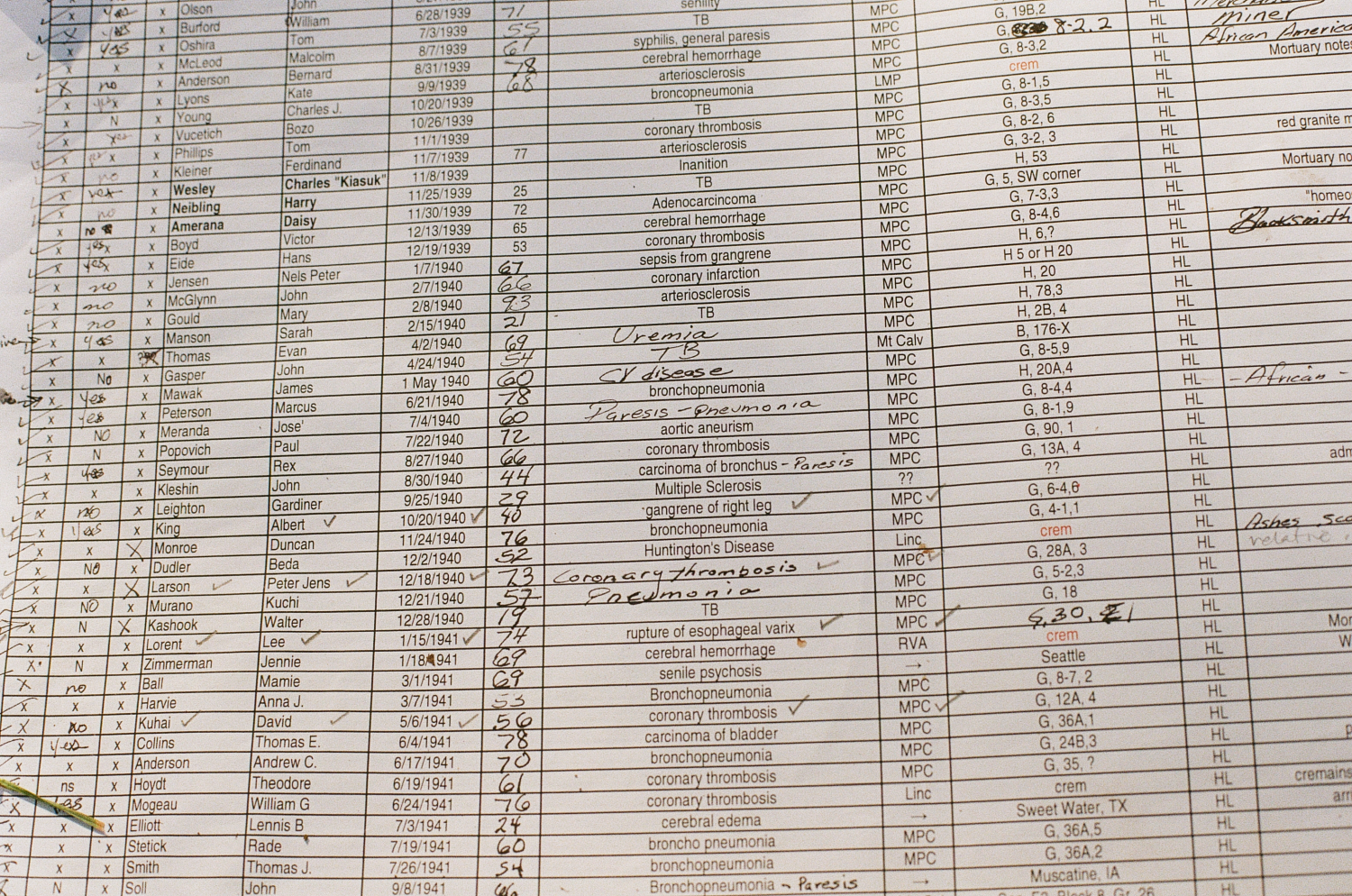

The picture of Morningside has come into focus thanks to the work of a group of volunteer researchers. The group, “The Lost Alaskans Project,” composed of two retired judges, a former state commissioner of health, and half a dozen others, spent the last 14 years piecing together the origin story of mental healthcare in Alaska. They combed through DOI quarterly reports at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., territorial court records in Alaska, death certificates in Salem, Ore., and cemetery records in Portland to tell the story of what happened to those labeled as the “mentally ill” of Alaska. They digitized their findings into an online database for relatives looking to locate their ancestors.

Offerings for children who died at Morningside Hospital and Baby Louise Haven, a separate institution in Salem, Ore. where parents sent their disabled children before such care was offered in state. Researchers don’t yet have a full accounting of children who died at Baby Louise Haven, which operated from about 1960 to 1974, because records are sealed for 75 years from closing. The difference between Baby Louise Haven (BLH) and Morningside is that babies born with disabilities were sent to BLH by their parents and the state, whereas those sent to Morningside were convicted of a mental illness and sent there by a six-person jury of white males and the federal government.

Of the more than 1,100 people who died at Morningside—of disease, accidents, and mistreatment—most remain buried across six different cemeteries throughout Portland in both marked and unmarked graves, according to research by Eric Cordingley. Cordingley is a Portland historian and cemetery volunteer who has hand collected the more than 1,100 death certificates from the Oregon State Archives.

Many records note patients’ cause of death as: “reaction to insulin”, a science-discredited psychological treatment hospital staff employed—many of whom lacked formal medical training—on psychiatric patients, where they’d administer insulin to induce comas. Additionally, Alaska Native patients were overrepresented in shock therapy treatment because a lack of English literacy was confused for a mental health diagnosis, according to one researcher’s analysis of quarterly reports.

“The difficulty of expressing oneself in a language one does not speak could very easily be misidentified as symptoms associated with dementia praecox, such as dull emotional affect and disjointed thought patterns,” researcher Shir Lev Bach wrote in his 2021 thesis on Morningside. “In fact, 5 out of 8 Native patients who received shock therapy received a diagnosis of catatonic dementia praecox, a sub-diagnosis characterized by ‘stupor, muteness, (…) and verbigeration [the repetition of random words].’”

About 30% of the total Morningside deaths identified to date were Alaska Native people. As was the case with Indian boarding schools, the families who lost children and adults to the institution were often left in the dark about the fate of their relatives.

That was the case for Irene Dundas and her family. Dundas flew in from Ketchikan for the Portland ceremony to learn more about her two known relatives buried at Morningside. She grew up hearing the family lore about her great grandfather, Charlie Williams, who was sent to Morningside for dementia. It wasn’t until she learned of the Lost Alaskans database that she realized her great grandfather was still buried in Portland, and that she might be able to bring him home.

“The Tlingit people have a very, very intense mourning process,” Dundas, a repatriation specialist for her tribe, the Ketchikan Indian Community, said. That process includes a 40-day ceremony after a death, followed by a koo.eex’ one year later, or a post-funeral ceremony, where mourning songs are produced and the grieving family’s opposite clans come to soothe them.

At Saturday’s ceremony, Dundas began a mourning song that Tlingit tradition dictates she can’t finish until proper protocols are followed for her Indigenous ancestors, including the high caste Tongass Chief, David Kinninook, who also died at Morningside. Kinninook’s records show he died at 70 of tuberculosis, and was buried at a local Portland cemetery.

“I’m going to sing a mourning song, but I cannot finish the mourning song,” Dundas said on Saturday. “At the end of the one-year ceremony is when you finish the song. Until then, I have to go back and inform the clans that their grandfathers are here.”

Naomi Michalsen (right) and her mother, Andria Moss. Moss is Tlingit, Filipino, and Japanese. Her Japanese grandfather was sent to a Japanese internment camp, and her Tlingit mother, grandmother, and other relatives were sent to Indian Boarding Schools. “In our family, we've been disconnected from our language, cultures, and families,” Michalsen said. “We know that a lot of our family was sent to these places. And we lost track of them.”

The ceremony was meant to honor spirits and offer healing to descendants of those who were lost, said Tlingit attendee Naomi Michalsen, from Ketchikan. Bob Sam invited Naomi to participate because she is his clan’s opposite, which is necessary to provide balance in the grieving.

“Today's ceremony is a journey from darkness to light, a journey from being lost to coming home,” said Michalsen.

But the long journey home has only just begun for the lost Alaskans.

Norene Otnes holding her grandson’s killer whale vest. Born a few generations earlier, she said her now ten-year-old grandson, who has cerebral palsy, would have been a candidate to go to Morningside or Baby Louise Haven. “When we have our koo.eex’, we bring our regalia so that we could support the people that have been lost,” Otnes said. “It was important for me to bring my grandson’s for the children who have not been able to wear it.”

A member of an international grandmother’s group in attendance, Norene Otnes of Juneau, Alaska, opened Saturday’s ceremony with a prayer for the lost children.

The former grounds of Morningside, now known as Mall 205. The hospital was torn down in 1969, and is now a shopping center, where empty parking spaces on concrete mirror cemetery plots.

GRIEVING ENDS, GRIEVING BEGINS

In 2021, the Department of the Interior began the first-ever investigation into its federal Indian boarding school system, including how many children passed through them, how many died there, and where they are currently buried. But asylums, including Morningside and Hiawatha Indian Insane Asylum in Canton, S.D., were left outside the scope of the investigation.

According to Department of Interior spokesperson Tyler Cherry, the federal government doesn’t have a count of how many psychiatric institutions it paid for or operated to treat American Indian and Alaska Native patients throughout the 20th century.

If the agency responsible for operating these institutions doesn’t have a full accounting of the scope of these institutions, repatriation and healing experts wonder: who does?

“If the government doesn't know and they are the ones who funded these institutions, then we’re in a real dangerous place,” said Deb Parker, CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS). “At the end of the day, the families deserve to know where their loved ones are buried.

Shannon O’Loughlin, chief executive officer of the Association on American Indian Affairs, said the federal government needs to account for every federally funded institution to better understand: how many Natives were sent there, how many died, and how they can be returned to their homes.

“The federal government must be held accountable for every instance a Native person was institutionalized because the person was Native,” O’Loughlin told Native News Online. “This not only happened with boarding schools, but also occurred with asylums that housed Native Peoples that were ‘mentally ill’, ‘unhoused, or ‘poor.’”

A full accounting of these institutions is the first step to bringing relatives home, she said. To date, only two Alaska Natives who died at Morningside have been returned back to their Alaskan homelands.

In both instances, lineal descendants learned of their respective grandmothers’ burials at Morningside. They then rallied their relatives to help pay for—and coordinate—the returns.

In 2001, Tlingit archeologist John Campbell first learned from a relative that his grandmother, Louise Hinchman (Tsu’si) wasn’t buried in Haines, Alaska, like he’d thought. Hinchman, an Eagle-Thunderbird Chilkoot Indian, spoke English and had worked as an interpreter for the federal courts when Alaska was still a territory, according to her great-granddaughter Harriet Brouillette.

In 1929, Hinchman’s white husband had her convicted of insanity and sent her to Morningside as a ploy to possess her land, Campbell said. She died of tuberculosis five years later and was buried at Multnomah Park Cemetery in Portland, according to her death certificate. The cemetery is owned by Metro Historic Cemeteries, a branch of the regional agency serving parts of three counties in the greater Portland area.

Campbell worked for almost two decades to bring his grandmother home. Initially, a Multnomah Park Cemetery employee, who later ended up in jail for embezzlement, quoted him $6,000 for Hinchman’s disinterment, Campbell said. Metro Pioneer Cemeteries required Campbell receive a court order from the Circuit Court of Oregon in Multnomah County allowing for the disinterment of his grandmother, and proving his relationship to her, a process that required he hire an attorney. Metro Historic Cemeteries charged Campbell $1,750 for his grandmother’s disinterment in 2018, according to documents obtained by Native News Online. In April 2018, Campbell and his daughter brought Hinchman from Portland, home to rest in Haines.

“It felt like she didn't belong in a pioneer cemetery, and (I) felt relieved when we had a re-burial ceremony [in Haines],” Campbell told Native News Online.

When relatives are re-buried at home, he said, people can go visit them.

Multnomah Park Cemetery, where more than 400 Morningside patients were buried from 1909 to 1942, according to records obtained by Cordingley. At least 425 remain buried here.

In September 2023, a family from Fairbanks also brought home their grandmother, Lucy (Pitka) McCormick from Multnomah Park Cemetery. Similarly to Campbell, Lucy’s grandson, Wally Carlo, only learned of his grandmother’s fate in 2023 from a cousin. Like so many others, his parents never spoke of his grandmother, who disappeared one day, and never returned.

Lucy was only 41 when she was convicted of dementia and committed to Morningside in 1930. She died 10 months later of an infection following a hysterectomy, her records show.

Almost a century later, Lucy’s grandson laments that a young woman underwent an invasive procedure that ultimately killed her, all in the name of stopping reproduction.

“That’s what they were doing,” Carlo, 77, told Native News Online. “Somebody needs to look closer at what happened.”

Carlo accompanied his grandmother’s remains back home from Portland, and took her from Fairbanks to her home village of Rampart by snowmachine, showing her all the places she grew up with almost a century earlier: the river, the mountains, the eagles.

“The day we took her over to the Yukon River Bridge, the swans and eagles putting on a show for her, 92 years later,” Carlo said. “It was emotional all the way through.”

Carlo said the total cost to bring his grandmother home was about $12,000, paid for between himself and his family. That’s not including the cost of her disinterment, a $3,000 expense that was covered by Metro Historic Cemeteries, he said.

In 2013, Carlo’s relatives attempted to repatriate another ancestor, Timothy Pitka—Lucy’s brother— from Greenwood Hills Cemetery in Portland. But Pitka’s grave was empty when his relatives opened it, due to poor record keeping and cemetery mapping, Cordingley said. Pitka’s family instead brought home soil from his empty grave to rebury in Fairbanks.

In order for additional families and tribes to bring relatives home in the future, there needs to be a clearer idea of who owns each cemetery, how federal repatriation law might apply, and what the next steps are, according to repatriation specialist Dundas.

“It's always been a gray area to repatriate human remains from the boarding schools, or [institutions like] Morningside because we don't know if they receive federal funding, or who owns [each cemetery now],” Dundas said. “It's just been difficult.”

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), the federal law that compels some museums and institutions to return Native American human remains and artifacts, doesn’t apply to relatives buried on private lands so long as those Indigenous relatives remain in the ground, according to National NAGPRA Program Manager Melanie O’Brien.

“In this case, if someone wanted to request an individual be exhumed, it would be up to the cemetery owner and the state law to decide if that could be done or not,” O’Brien said. “Nothing in NAGPRA requires disinterment.”

The Department of Interior encourages the current owners of boarding schools and cemeteries to fully consult with lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian Organizations on identification, disinterment, and repatriation of Native American children, she added.

Prayer ties from the March 9th honoring ceremony. Attendees were instructed to place one in their pocket, and take it out when they were ready to release their grief.

George Holly (right), an Athabascan from the Lower Yukon, led the group in Tlingit dances he teaches his students at Glacier Valley Elementary School in Juneau, Alaska.

'IF YOU LOOK, YOU'RE GOING TO FIND IT'

Within four days of the honoring ceremony, the Ketchikan Indian Community had already identified dozens of additional relatives buried at Morningside.

At Dundas’ urging, Ketchikan-based historical researcher Sid Hartley used the Lost Alaskans database to curate a list of more than 60 Alaska Native relatives from Southeast Alaska who are buried at Morningside.

Hartley was also able to match names on historic deed sales, with names of local residents who were committed to Morningside, calling into greater question the true reason for sending Alaskans to the asylum in the first place.

“I have a whole binder of deeds and all of these land sales that I found through research last year,’ said Hardley. In 2023, she was asked by a Ketchikan Indian Community clan leader to research land grabs in their community, including by reading through more than 500 pages of Tlingit landowner testimony from a 1901 local land case. “And, sure enough, there are some names correlating with their date of internment into this asylum.”

Ketchikan Indian Community Vice President Gloria Burns expects this connection of Native land dispossession with Alaska Natives removal from their homelands under the guise of mental health treatment, to become more apparent with further research.

“I think when you look, you're gonna find it,” Burns said. “When we look through this, we're going to see not just allotment issues, but I think particularly we'll find women and children who had land, who suddenly didn't have land anymore.”

Ketchikan Indian Community Vice President Gloria Burns (left) beside tribal repatriation expert Irene Dundas (right). The two stressed the importance of following tribal and clan protocol in the process of mourning their relatives.

Irene Dundas’ necklace on Saturday, March 9, was made from trade beads that were previously looted from cultural heritage sites in Ketchikan and Saxman, Alaska. The beads were repatriated to a group who then gifted them to Dundas for her work in returning Alaska Native ancestors and their belongings.

'LOST, NOW FOUND'

Eric Cordingley spends several hours each week unearthing ancient headstones that have been, as he puts it, “turfed over.” He's ultimately creating a repatriation roadmap for families by maintaining the Multnomah Park Cemetery.

On a sunny March afternoon, Cordingley is out at the cemetery with his tools: a bucket, a hand broom, a soil probe, a crow bar, and massive spreadsheets noting each recorded patient’s death, along with where they’re buried.

In the back row of the cemetery, where the Morningside patients lay underground, he counts three paces between where headstones should be, but overgrown grass has disguised many of them. When he successfully locates a stone using a long cylindrical soil probe, he uses a crowbar to unearth it from several inches in the ground, dust it off, and place it back atop its grave.

Eric Cordingley, a Portland resident who has worked collecting death certificates of Morningside patients from the Oregon State Archives for more than a decade. After locating the records, Cordingley then searches for its corresponding headstone in the Morningside cemeteries, and uploads a photo for each grave he locates to an online database, where families can locate their relatives.

When he locates a headstone that matches his records with a Morningside patient, he takes a photo and uploads it on FindaGrave.com for families to more easily locate relatives. He’s been building the online grave repository for more than a decade.

But not all six cemeteries where Morningside patients were buried were plotted as neatly as Multnomah Park Cemetery.

Nine miles away, at the now privately owned Greenwood Hills Cemetery, more than 230 Alaska Native and non-Native patients are buried in unmarked “pauper graves” in a section of the cemetery that appears like a forest among otherwise neatly maintained headstones and freshly mowed grass.

George Shakes is buried here, the great grandfather of Trixie Bennett, a Tlingit woman and tribal health administrator from the Ketchikan Indian Community. Bennett attended the Portland ceremony to learn more about her grandfather, who her family tried to repatriate in the early 1990s. A cemetery employee at the time told Bennett’s family that Shakes was buried in an unmarked grave.

The day following the honoring ceremony, Bob Sam and his daughter, Birdie Sam, went to the Greenwood Cemetery to confirm Shakes’ fate themselves. Cordingley showed them a swath of land where he’s buried — the “notorious” Section 8 of the cemetery, where more than 230 unmarked graves of Alaska Native and non-Native Morningside Patients remain buried in an overgrown forest, without any markers or headstones.

According to Cordingley, Greenwood is the worst cemetery in the city’s roster of 28 total graveyards, for the way it was poorly plotted, and then not maintained.

The “notorious” Section 8 of Greenwood Cemetery, where more than 230 unmarked graves of Alaska Native and non-Native Morningside Patients were buried without a plot map or headstones, making it nearly impossible to locate and bring home relatives, Cordingley said.

“No wonder they call it the Lost Alaskans,” Sam says, pointing to the mile of overgrown brush beside immaculately trimmed grass, where others are buried. “These are all bodies. It doesn't matter if they’re Native or not. This is a crime.”

Retreating from the mass gravesite in the spitting rain, Sam leaned in to ask Cordingley a question.

“How did they get away with this?” Sam, who speaks in a low timber, said.

“Nobody was watching, Bob,” Condingley replied. “That’s how.”

Ultimately, Saturday’s ceremony was about finding more than the Lost Alaskans, attendees said. It was an opportunity for family members to reconnect. Sam and his daughter haven’t been in touch for years, she said. After attending the honoring ceremony, Birdie Sam said she has a greater understanding of—and appreciation for—what has captured her father’s attention all her life.

Eric Cordingley (left) walks the grounds of Greenwood Cemetery with Bob Sam on March 10.