- Details

- By Professor Victoria Sutton

Guest Opinion. Traditional ceremonies to welcome a new year have been carried out by Native American Native Nations since long before the arrival of the colonists and the establishment of the United States.

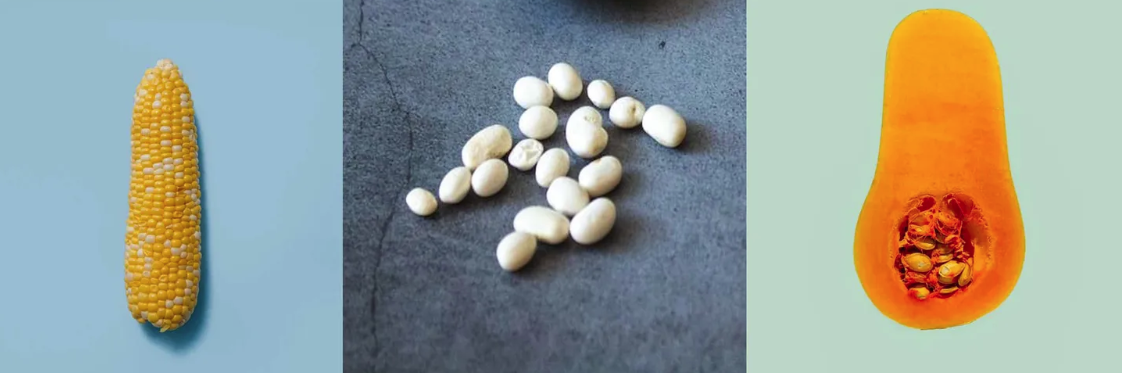

The Native American celebrations take place in December, January or February, typically in relation to the winter solstice (around December 22). For the Hopi, the New Year is welcomed with the Soyal Ceremony that lasts nine days and represents the second phase of the Hopi creation story. The Hopi dance is directed to turning the sun back toward summer where life can flourish again. The Tuscarora and other Iroquois tribes celebrate a midwinter festival, set during the first full moon after the winter solstice. This comes at the end of January or beginning of February and involves ceremonies in the longhouses and collection and sharing of traditional foods considered sacred, like corn, beans and squash. The Umatilla in the northwestern U.S., gather these traditional foods and recognize when their ancestors complete their lives and return to the earth, this is the way the ancestors care for their descendants. These ceremonies and others were considered important not only to the Native Nations continued existence but to that of the world.

Make A Donation Here

Make A Donation Here

But when officially declared war by the U.S. against Native American Native Nations failed to destroy them, the U.S. next declared war against Native American Tribal culture. If the U.S. could destroy the culture, they could destroy the Native Nations, they reasoned. To that end, in 1883, Henry Teller of the Depart of Interior, sent a letter to Hiram Price, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and explained why he was imposing this new Code of Criminal Offenses in the Courts of Indian Offenses (operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs where Tribal Nations had no court systems).

SIR: I desire to call your attention to what I regard as a great hindrance to the civilization of the Indians, viz, the continuance of the old heathenish dances, such as the sun-dance, scalp-dance, & c. These dances, or feasts, as they are sometimes called, ought, in my judgment, to be discontinued, and if the Indians now supported by the Government are not willing to discontinue them, the agents should be instructed to compel such discontinuance. These feasts or dances are not social gatherings for the amusement of these people, but, on the contrary, are intended and calculated to stimulate the warlike passions of the young warriors of the tribe.

The tone of this letter reflects the fear the U.S. had about the resilience of the Native Nations. Across the United States, Native Nations had simultaneously started a revival of their dances and traditions in what looked to the military like preparations to retake the United States land that had been lost to colonists and settlers. To enforce this draconian lock down of traditions, the letter then outlined categories of crimes and their punishment. Participating in dances and ceremonies could warrant up to a month without food rations. Agency superintendents had the authority under this code to stop any practices that they felt were immoral or counter to furthering assimilation or genocide of Native Nations and their people.

Dances were specifically named but extended to any other dances or feasts:

The "sun-dance," the "scalp-dance," the "war-dance," and all other so-called feasts assimilating thereto, shall be considered "Indian offenses," and any Indian found guilty of being a participant in any one or more of these "offenses" shall, for the first offense committed, be punished by withholding from the person or persons so found guilty by the court his or their rations for a period not exceeding ten days; and if found guilty of any subsequent offense under this rule, shall be punished by withholding his or their rations for a period not less than fifteen days, nor more than thirty days, or by incarceration in the agency prison for a period not exceeding thirty days.

Further, any activities of a Medicine Man that tended to encourage participation in ceremonies was also criminalized:

The usual practices of so-called "medicine-men" shall be considered "Indian offenses" cognizable by the Court of Indian Offenses, and whenever it shall be proven to the satisfaction of the court that the influence or practice of a so-called "medicine-man" operates as a hinderance to the civilization of a tribe, or that said "medicine-man" resorts to any artifice or device to keep the Indians under his influence, or shall adopt any means to prevent the attendance of children at the agency schools, or shall use any of the arts of a conjurer to prevent the Indians from abandoning their heathenish rites and customs, he shall be adjudged guilty of an Indian offense, and upon conviction of any one or more of these specified practices, or, any other, in the opinion of the court, of an equally anti-progressive nature, shall be confined in the agency prison for a term not less than ten days, or until such time as he shall produce evidence satisfactory to the court, and approved by the agent, that he will forever abandon all practices styled Indian offenses under this rule.

But punishment was not limited to simply withholding rations. It was this code that led to the Massacre at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890 on the Pine Ridge reservation all because they were dancing the Ghost Dance (also the Sun Dance). Almost 300 elders, women and children were killed by the U.S. Army without provocation, including the beloved elder Lakota Chief Spotted Elk. Buried frozen, the next day, from the killing field were 84 men, 44 women and 18 children. The leaders of the U.S. Army carrying out this slaughter of defenseless elders, women and children were awarded military medals of honor, which have still not been rescinded or condemned to this day, even during a weak apology from Congress on the 100th anniversary of the slaughter in 1990.

One might think that the United States would have seen the wickedness and immorality of their slaughter of innocent people and quickly reject these codes of Indian offenses -- but that would be wrong. It was not until 1933, when John Collier became Indian Commissioner that the criminalization of dances and other traditional activities in the Code were eliminated. Thereafter, there was interest in protecting indigenous traditions maintained by a growing number of Americans, yet it was almost a century before these laws would be officially superseded by legislation. Not until 1978 were these laws officially and legally superseded by legislation that removed the prohibition against Native Americans practicing their ceremonies and traditions, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. Today, the battle for religious freedom and the practice of traditions and ceremonies tied to the land is still being fought for Native Nations, the First Amendment protecting religious freedom as analyzed by the U.S. Supreme Court continues to fail Native Nations.

Today, Native Americans and Native Nations have reestablished or continued their ceremonies and celebrations of the winter solstice and its relationship to the New Year. If you are fortunate enough to be in the Albuquerque region, some of the Tewa Pueblos have opened their New Year ceremonies to the public. Anywhere, you might find individual Native Americans incorporating tribal traditions into the New Year celebration with a collection of sacred foods. Collecting squash, corn and beans, the traditional “three sisters,” to share with family and friends is a good start to 2023.

Happy New Year!

To read more articles by Professor Sutton go to: https://profvictoria.substack.

Professor Victoria Sutton (Lumbee) is a law professor on the faculty of Texas Tech University. In 2005, Sutton became a founding member of the National Congress of American Indians, Policy Advisory Board to the NCAI Policy Center, positioning the Native American community to act and lead on policy issues affecting Indigenous communities in the United States.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher