- Details

- By Elisa Xu

When Theresa Dardar, a member of the Pointe au Chien Indian Tribe, first caught wind of Hurricane Ida's trajectory towards coastal Louisiana, she planned to stay with her brother's family in Houma, Louisiana to wait out the storm. But as she kept watching the news, she started to think that maybe Houma — a city 30 miles from the coast — wasn't far enough.

Her brother was on the same page. He called, saying his wife had found a single hotel room where they could seek shelter. The only available room she could find was in Texarkana, Texas, more than six hours away.

Dardar and her husband started their long drive towards shelter on Saturday, Aug. 28, 2021 at 8:30pm. When they finally arrived at 3 am the next day, Dardar and her husband crowded together with her brother, her sister-in-law, her granddaughter, and their two dogs in the hotel room as they waited for the Category 4 storm to subside.

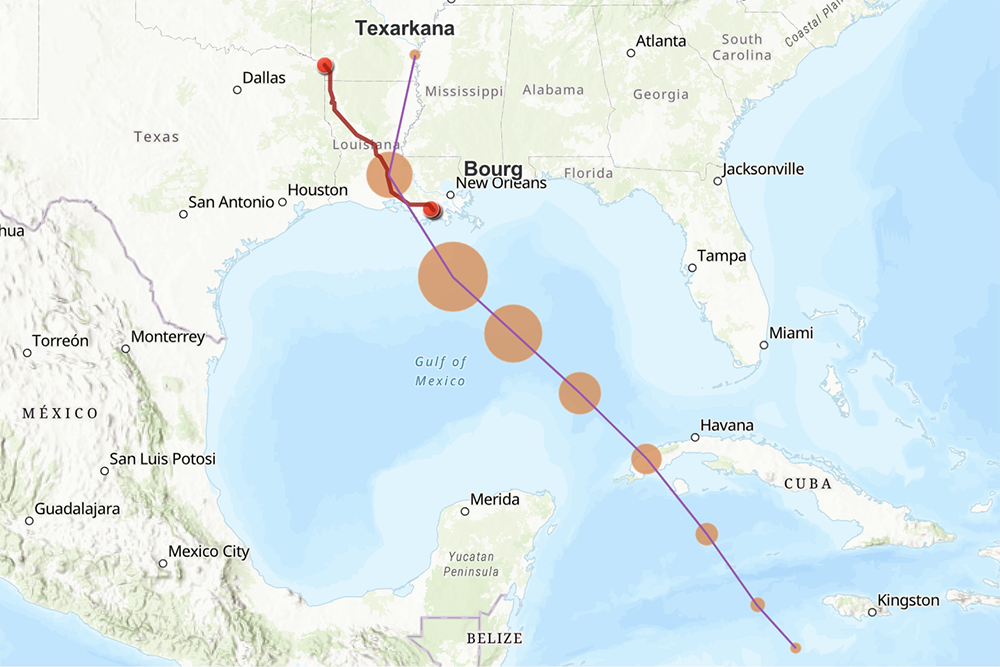

This map outlines a possible path Theresa Dardar could have taken when she drove from Bourg, Louisiana to Texarkana, Texas to seek refuge from Hurricane Ida's path. She realized that Houma, Louisiana, her original evacuation destination, wouldn't be far enough. (Map from ESRI)

This map outlines a possible path Theresa Dardar could have taken when she drove from Bourg, Louisiana to Texarkana, Texas to seek refuge from Hurricane Ida's path. She realized that Houma, Louisiana, her original evacuation destination, wouldn't be far enough. (Map from ESRI)

Hurricane Ida was one of the strongest storms to hit Louisiana since the 1850s. It made landfall near Port Fourchon on Sunday, Aug. 29, 2021 with sustained winds of 150 mph. The storm continued inland, bringing with it catastrophic winds, intense rainfall and tornadoes.

The coastal region of Louisiana, which many Indigenous tribes call home, was hit especially hard. The Pointe au Chien tribe is located in Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. Between these two parishes, 12,000 temporary shelters were needed for displaced residents. Terrebonne local officials estimated in late September that 60% of homes in the southern part of the parish were uninhabitable.

Dardar drove back towards her home in the Pointe au Chien community on the Wednesday after the storm, waiting for the water in the roads to go down. When she got off highway 90, she started seeing the extent of Ida's aftermath.

“And I just in my mind thought, 'Oh my god, do we even have a community left?'” Dardar said.

Destruction from right after Hurricane Ida. (Photo/Courtesy Theresa Dardar)

Destruction from right after Hurricane Ida. (Photo/Courtesy Theresa Dardar)

From up the bayou, she didn't see a single house that wasn't damaged. While some were still livable, many suffered damage so severe that they were uninhabitable.

“That Wednesday I just sat on my porch, and I cried,” Dardar told me. “It still hurts.”

But despite the devastation from increasingly strong hurricanes like Ida, Dardar — like many in the Pointe au Chien Tribe — is committed to staying to build her community. Dardar only knows of one couple from Pointe au Chien who plans to relocate after the hurricane. She points to a sense of connection to the resilience of her ancestors for why people resolve to stay.

“I'm sure every time there was a storm, probably just strong winds, maybe not even a hurricane, [our ancestors] had to rebuild their… huts,” Dardar said. “They were always a strong people.”

The approach to rebuilding versus relocation varies throughout the Indigenous tribes in the area. The Deputy Chief from the nearby Grand Caillou/Dulac Band Tribe, who opted to use only her title for this story, says she and Chief Shirell Dardar-Parfait have long-term plans to relocate the entire tribe up north, further away from the water. In the meantime, however, they still plan to build a community center on a plot of land in the community to provide a space for tribal members to gather together.

The Grand Caillou/Dulac Band tribe hopes to build a community center on a currently mostly empty lot. After the hurricane, tribal members have scattered and don't have a central place to come together. (Photo/Elisa Xu)

The Grand Caillou/Dulac Band tribe hopes to build a community center on a currently mostly empty lot. After the hurricane, tribal members have scattered and don't have a central place to come together. (Photo/Elisa Xu)

The deputy chief said since she's of a younger generation and has young children, she understands the need to relocate. But she says she still feels conflicted.

“Some days I'm with it, some days I'm not. It's like a culture shock to me, to go somewhere, especially when you don't have water,” The deputy chief said. “Which that's technically what we're trying to do, get out of water. But when that's all you've known all your life…”

For Pointe au Chien Tribe, only 12 out of 80 homes were livable immediately after the storm according to Dardar. Many people didn't get temporary housing, such as FEMA trailers, until four months afterwards.

Federal assistance has been slow to reach many coastal Louisiana tribes — including Pointe au Chien and Grand Caillou/Dulac Band — because they are state recognized, not federally recognized. This means they can't access the benefits offered to federally recognized tribes.

Federally recognized tribes are treated as sovereign nations within their state. They can directly negotiate aid with the federal government and can oftentimes more quickly deliver assistance to their communities. In contrast, state recognized tribes must apply for aid like regular citizens. According to FEMA's website, federally recognized tribes can request a Presidential emergency or major disaster declaration independent of a state. State recognized tribes cannot.

Only four out of the 15 tribes in Louisiana are federally recognized, and many have been in the process of appealing for federal recognition for decades to no avail.

In the aftermath of Ida, Dardar says that she and her husband, Donald Dardar, were lucky that their house suffered only relatively minor damage. The back of their house was the only part damaged, caused by her mother-in-law's house's roof blowing off and colliding with their house during Ida. Her husband had installed a shingled roof after damage caused by Hurricane Gustaf in 2008 and later, he installed another metal roof on top of the shingles. This had protected them from rain damage during Ida.

“But thank God. I felt that there was a reason that my house wasn't [badly] damaged.” Theresa Dardar said. “I believe it was for me to be there for our tribal people.”

In the short term, the process of rebuilding included making sure people had enough to survive. In the days and weeks after Hurricane Ida, the Dardars worked to collect, organize, and distribute the donations that came streaming in from across the United States. Setting up the donations at the Pointe au Chien Tribal Center, they served their tribal members along with anyone else in need after the storm. From necessities like food, diapers and cleaning supplies to canisters of gas, generators and tarps, people could come in and take whatever they needed.

Sometimes, people just needed a space to sit down and talk.

“You know, they didn't have a home to visit people anymore. So, it became the meeting place,” Theresa Dardar said.

Louisiana's high rate of coastal erosion has made hurricanes like Ida only more severe. According to New Orlean's Hazard Mitigation Plan from 2020, Louisiana has the highest rate of wetland loss in the United States, accounting for 80% of the nation's coastal wetland loss. The United States Geological Survey states Louisiana has lost around 1,900 square miles of land along its coast since 1932.

Since wetlands act as a buffer to reduce the wind speeds and storm surge heights of hurricanes, communities are facing increasingly higher risk from storms as the wetlands continue to disappear.

Maps hanging on the walls of the Pointe au Chien tribal center show how the lakes and bays around the community used to be well-identified. Behind Dardar's house, there used to be enough land for her ancestors to trap animals like muskrats. Now, the area is filled with water deep enough to fish in.

More destruction from Hurricane Ida. (Photo/Courtesy Theresa Dardar)

More destruction from Hurricane Ida. (Photo/Courtesy Theresa Dardar)

Oil companies have a large role in the state of coastal erosion. By cutting canals along the coast to make room for their boats to collect oil without refilling these canals afterwards, the companies have left the cuts to widen and accelerated coastal erosion. One of these cuts has caused one of Pointe au Chien's mounds — pieces of land that current tribe members' ancestors built up by hand for purposes ranging from ceremonial to burial — to start washing away.

For the Pointe au Chien tribe, the approach for rebuilding is inherently tied to preventing further coastal erosion and protecting their cultural heritage. In an example of protecting both cultural heritage and land, the tribe built a “living shoreline” around one of their mounds in 2019.

Donald Dardar had noticed that one of the tribe's mounds had been washing away for years. He asked around for help to preserve the land, talking to practically everyone he met, for around three years to no avail.

“He was at the point where he said, 'If I have to, I'm going to just buy plywood and go try to save it myself,'” Theresa Dardar said. “Because we hate it, watching it just wash away.”

Finally, he got in contact with a worker at Lafourche parish who was able to secure a grant to protect the mound. After another three years, the work began in earnest. In collaboration with the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana, the tribe helped implement a Living Shoreline project, a project where workers collected oyster shells from New Orleans restaurants and placed bags of them around the mound. Oysters and oyster reefs help improve water quality, create a shoreline habitat, and help prevent further land loss. It's called a living shoreline because oysters grow on top of the recycled shells, while also attracting crabs and fish to feed on the oysters.

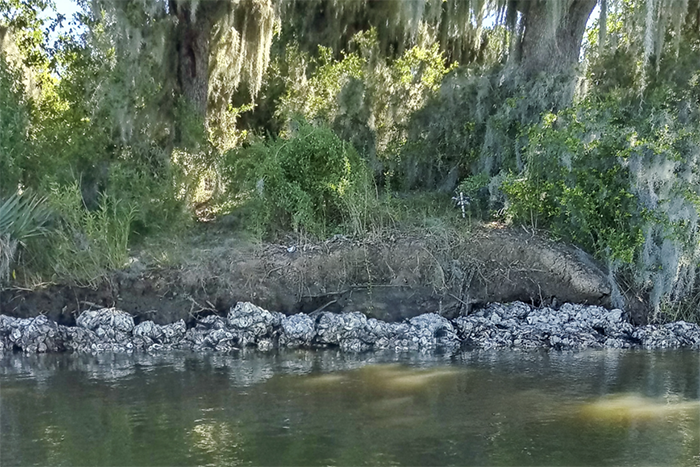

CRCL and the Pointe au Chien tribe built this Living Shoreline project around one of Pointe au Chien's mounds to fight erosion and promote biodiversity. (Photo/Courtesy Theresa Dardar)

CRCL and the Pointe au Chien tribe built this Living Shoreline project around one of Pointe au Chien's mounds to fight erosion and promote biodiversity. (Photo/Courtesy Theresa Dardar)

“They've been there since Hurricane Ida, and it held up very well,” Theresa Dardar said.

Seeing the success of this project, Donald Dardar is now in talks with CRCL to create another living shoreline project in another area of the coast, to protect more land.

And while their efforts to protect their land have been filled with uncertainty and increasingly volatile weather conditions from climate change, Pointe au Chien tribe members are still determined to stay and rebuild.

“People still stay. I mean…they don't know how they're going to do it. But…they're going to find a way to stay,” Theresa Dardar said.

Elisa Xu is a graduate student at Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism. She is passionate about highlighting the stories of communities of color and other traditionally underrepresented groups in the media.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher