- Details

- By Elyse Wild

A group of children from the Pala Band of Mission Indians was walking home from school in 2016 when they found a plastic bag holding 100 bright blue pills.

The kids tossed the bag back and forth as they walked to the tribe’s youth center, where they turned it into the staff.

The staff at the youth center quickly called law enforcement, who informed them the pills were fentanyl, a highly potent synthetic opioid 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine.

That same year, 16 youths from the Pala Band of Mission Indians died of opioid overdoses. For the California tribe — which has a population of around 1,000— the losses were a devastating sign that the opioid epidemic had gained footing in their community.

“They were our family members, cousins, relatives — it was a big eye-opener,” Pala Band Chairman Robert Smith, who lost two young cousins to opioid overdoses, told Native News Online.

Last month, the Pala Band took an innovative and important step to address the deadly opioid problem, installing a vending machine that dispenses a life-saving drug called Naloxone, which is more commonly known by the brand name Narcan.

The machine, situated at the Tribe’s fire department, has all of the appearances of a typical vending machine that sells soda, chips or candy. Behind the plexiglass front window of this machine, though, 100 vending slots hold doses of the Narcan drug, which can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose within minutes. Users scan a QR code on the machine with their cell phone, and the machine dispenses a free dose.

Pala Band Chairman Robert Smith, who lost two young cousins to opioid overdoses, stands alongside the new Narcan vending machine at the Tribe’s fire department. (Photo: Courtesy of Pala Band)

Pala Band Chairman Robert Smith, who lost two young cousins to opioid overdoses, stands alongside the new Narcan vending machine at the Tribe’s fire department. (Photo: Courtesy of Pala Band)

Naloxone works by blocking the effects of opioids on the brain and restoring breathing. It is highly effective, reversing up to 93% of overdoses. Part of what makes it so effective is that it people can easily administer it.

The drug has proven essential to decreasing the mortality rate from opioid use. Increased distribution of Narcan among community members and first responders could prevent 21% of opioid overdose deaths, per the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

“We are trying to be preventative out here because we have lost so many lives,” Smith said.

“We are not going to stop it [opioid use], but we have to do something for prevention and to save people’s lives.”

The Pala Band’s vending machine was funded through San Diego County’s Naloxone Distribution Program, and is part of a nationwide trend of communities embracing harm reduction strategies and making Narcan accessible to community members.

Harm-reduction measures like the Pala Band’s vending machine are critical for Native communities — where opioid use is significantly higher than in other parts of the country, according to Arlene Brown, Bishop Paiute Tribe, who works as a recovery coordinator in a California hospital.

“None of us are not affected by this crisis,” Brown told Native News Online. “When we talk about it, these are people we know — sisters, uncles, relatives. You’re connected to them in some way, and that is a lot of loss and grief for a community to bear.”

Unprecedented Rates

More than 103,000 Americans died in opioid-related incidents in 2022, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). That’s up more than 200% since 2000, according to CDC data.

While Americans of all races and ethnicities have been affected, the proliferation of opioid deaths has disproportionately affected Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities, especially Indigenous people. In 2020, Native Americans’ opioid mortality increased 39% over the prior year — the second-highest rate of increase behind African Americans, according to the CDC.

Generational trauma and barriers to healthcare access rooted in geographic isolation have left tribal nations reeling under the weight of opioid addiction, which is killing Native people at unprecedented rates. Native Americans disproportionately struggle with the comorbidities of opioid abuse: the Indian Health Service reports that Indigenous peoples experience higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is predominant in opioid dependence.

Tribes are fighting back against rising opioid use with harm-reduction, an evidence-based approach that seeks to mitigate the negative impact of drug use through syringe exchange services, Narcan access, fentanyl testing strips and more.

That approach is well-suited for Native communities, according to Brown, who works as recovery coordinator for the Northern Inyo Hospital in the Eastern Sierra town of Bishop Calif.

Breaking the Silence

Brown never intended to work in harm reduction.

When she returned home to the Bishop Paiute Reservation in 2018 after getting a master’s degree in addiction psychology from the University of North Dakota, she worked as the social services director for her Tribe.

After her best friend’s sister died of an overdose, she took it upon herself to start a conversation among her tribe about opioid use.

“All of a sudden, it was like someone shook me and said, ‘You know what to do,’” Brown said. “I wanted to break the silence and let people know that Narcan was available in our pharmacy.”

Two weeks after her friend’s sister died, Brown organized an event to address the Tribe’s opioid crisis. About 80 community members showed up.

“The opioid epidemic here wasn’t being talked about,” Brown said. “We had to ask, ‘What is being done about this?’ And take action, and then it just snowballed.”

Since then, Brown has led efforts to bring a harm-reduction approach to her community, launching a needle-exchange program called “Skoden” in 2019 and spreading the word about Narcan and distributing it in her community.

Since 2018, some 70 drug overdoses have been reversed with the Narcan made available by Brown’s efforts.

“I came home to do other things,” Brown said. “And I am so grateful I did come home.”

Evidence shows that harm-reduction is effective not only in reducing deaths and infectious diseases related to opioid use, but in stopping opioid use overall.

According to the CDC, people who use needle-exchange programs are five times more likely to enter drug-treatment programs and 3.5 times more likely to stop injecting drugs.

Laura Guzman is the Executive Director of the National Harm Reduction Coalition (NHRC), an organization founded in 1993 to advocate for those left vulnerable from drug use.

Guzman has been involved with the NHRC since 1995, working at the organization’s San Francisco branch, then as the NHRC director for California in 2020 before becoming executive director earlier this year. She saw firsthand the rapid spread of HIV through syringe-drug use during the AIDS epidemic and the skyrocketing mortality rates among opioid users as illicit fentanyl began flowing into the U.S. drug supply around 2014.

“We believe that acknowledging why people use drugs goes a long way in not only fully understanding the struggle for people, but also helping them to make the changes that they so choose to make at the time of pace that is possible for them,” Guzman said of the harm reduction approach.

She notes that the positive impact of harm reduction— which elevates the human dignity of drug users and meets them where they are—is amplified when integrated with cultural components, especially in Native communities.

“We need to allow for communities to take leadership in their healing experiences,” she said. “People have been colonized, erased from public health. Native-led health for natives feels comfortable and is important — it’s in contrast to the historical trauma of colonization.”

Indigenizing Harm Reduction

This month, the NHRC is launching a Native Harm Reduction Toolkit, created in collaboration with Brown. The toolkit — created through interviews with native healthcare leaders and tribal communities —serves as a guide to “Indigenize” harm reduction by infusing language, cultural values, and connection to community and self into services and treatment options.

“For me, this approach is really dismantling the Western approach of dealing with our own people,” Brown said. “We have a different way to engage with our people out here to show them love and to keep them safe. One of the biggest pieces for me is connecting them with culture so they’re not further isolated.”

As tribal nations deal with the drastic spike in opioid-related deaths in recent years, several have adopted harm-reduction strategies.

In 2022, the Blackfeet Nation of Montana declared a state of emergency after a rash of opioid deaths, creating a task force to drive efforts to distribute Narcan and host needle exchanges.

Earlier this year, Cherokee Nation announced the opening of a $3 million harm-reduction clinic in the Nation’s capitol of Tahlequah, Oklah.

This spring, Northern Wisconsin’s Bad River Band of Lake Superior Indians’ needle exchange program, Gwayakobimaadiziwin, partnered with online and mail-based harm reduction service NEXT Distro to be a Narcan distribution center for the state — where opioid overdose deaths increased by 900 percent in the past decade. Now, any Wisconsin resident can order through a website and receive free Narcan, clean syringes and fentanyl test strips in the mail.

The tribe launched Gwayakobimaadiziwin in 2015 and, in 2018, was awarded a two-year-policy grant through the AIDS United Access Fund to shore up efforts to treat opioid abuse in the community.

Bad River Economic Development Coordinator Philomena Kebec said the NEXT Distro partnership is in line with providing access to life-saving services while allowing drug users to keep their identities anonymous and stay out of the criminal justice system.

She notes historical discrimination in the healthcare system and the criminal justice system has exacerbated the impact of opioid abuse among Native Americans as people are driven to self-medicate to lessen the symptoms of trauma or avoid engaging with a system that wasn’t built for them.

“People struggle with mental health, with PTSD, and they are really unable to bridge the divide between themselves and the health care system that oftentimes just treats people like a widget,” Kebec said. “And we are significantly targeted by the criminal justice system. We really need to challenge the criminal justice model and look at other ways to think and feel about this issue… there is nuance involved.

“There are amazing people in my community who use drugs. We are not going to get beyond this until we start having more compassion and understanding why people are using drugs.”

‘Out here, discrimination kills’

Brown says that creating access to Narcan in Indian Country is crucial to giving Native communities a fighting chance — as is addressing the stigma that the life-saving drug may encourage opioid use.

“We need to saturate communities with Narcan,” Brown said. “You never know when you might be a first responder and save someone’s life. We really work on destigmatizing Narcan as ‘a drug for a drug.’”

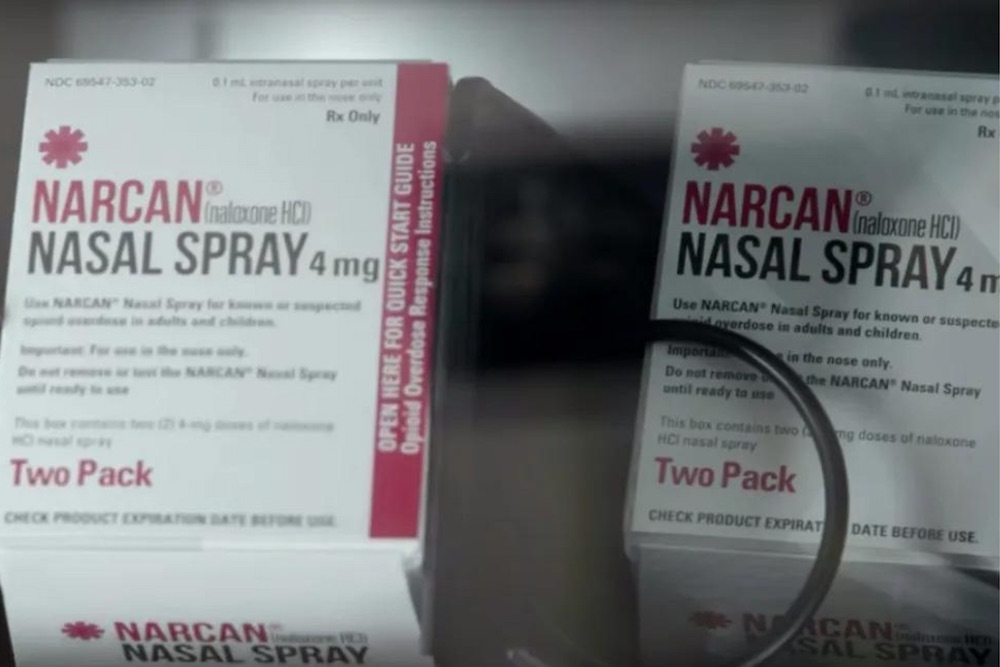

Shown: a photo of the Narcan packages in the Pala River vending machine. (Courtesy photo)

Shown: a photo of the Narcan packages in the Pala River vending machine. (Courtesy photo)

At the time of this interview, Brown had recently returned from the National Indian Health Board Conference (NIHB) in Anchorage, Alaska, where she said she heard over and over again that tribal communities are burying their loved ones at such a relentless rate there is barely space for grief.

“People don’t have time to grieve anymore,” Brown said. “They are losing people so fast. We need to take action in our communities ... Native Americans are discriminated against in so many ways, and out here, discrimination kills.”

Back on the Pala Band Reservation, Chairman Smith and tribal leaders are working to spread the word about the Narcan vending machine.

"We want to let everyone know that this is available — everyone, grandmas, grandpas, kids,” Smith said. “These drugs are killing people, and Narcan can save someone’s life.”

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

Seven Deaths in Indian Country Jails as Inmate Population Rises and Staffing DropsSen. Luján Convenes Experts to Develop Roadmap for Native Maternal Health Solutions

Senate Passes Bill Aimed at Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples Crisis

Johns Hopkins Collecting Tribal Success Stories from $1.5B Opioid Settlement

Arizona MMIP Task Force Holds Listening Session for Survivors and Families