- Details

- By Lynn Liu and Pingping Yin, Special to Native News

CHEROKEE, N.C. — When Dawn Arneach was a teenager in the ‘80s, she spent summers at her grandparents' house next to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Cherokee, home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Despite all the time she spent with her grandparents, Arneach had no clue that they were fluent Cherokee speakers until her grandfather fell seriously ill. She was surprised when she overheard him speaking fluently in Cherokee with a visitor.

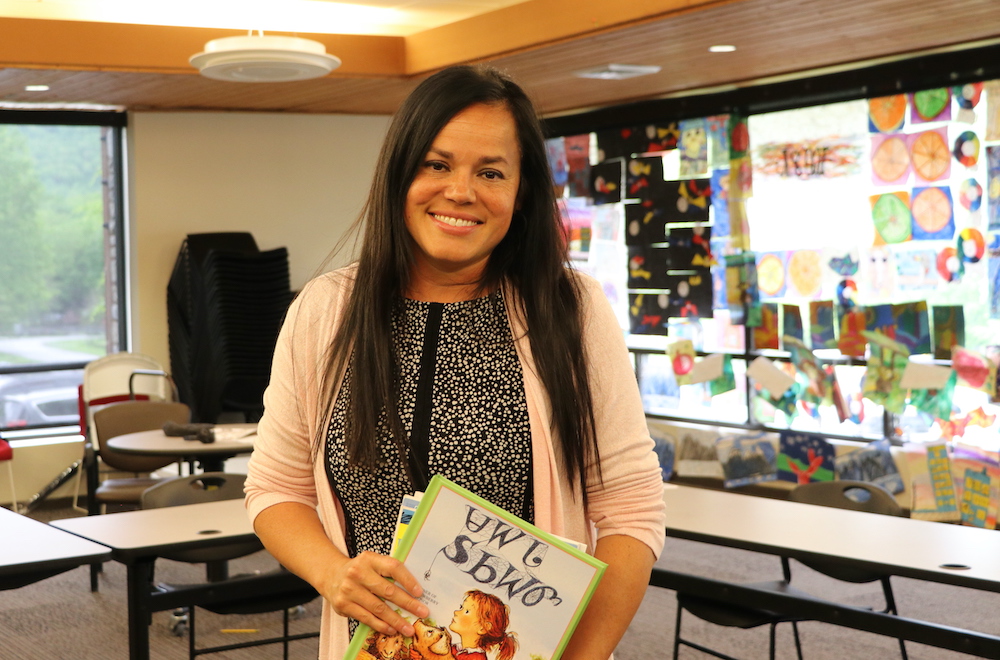

After her mother passed away in 1991, the then 23-year-old Arneach decided to move from Georgia to Cherokee to reconnect with her ancestral roots in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Years later, she started to take Cherokee language classes together with her second son, Landon French. Now, after continuing his language education in college, French is a teacher at New Kituwah Academy Elementary, teaching Cherokee. At home, he has two more students: His daughter and his mom.

“Now that he's a teacher at the school, and my granddaughter is a student in the school, they have more language than I did and more language than my dad had,” Arneach, an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee, said. “So for me, it's like coming full circle finally in our family.”

Arneach is learning the language with her granddaughter, and they play language games together at home. Arneach said one important motive for her continued enrollment in language classes is the desire to communicate more frequently with her granddaughter in Cherokee.

There were 9,600 people living on the Eastern Cherokee Reservation with only around 189 fluent Cherokee first-language speakers among the population, according to the U.S. Census and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. That’s less than 2% of the whole population. The New Kituwah Academy is an example of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ effort to greatly increase the number of fluent speakers and revitalize their language before it’s too late.

Revitalizing Native American languages is urgent post-COVID-19, as many elders who spoke their Native languages passed away during the pandemic. Out of the 300 Indigenous languages once spoken in the U.S., only 175 languages remain today, according to the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (AIHEC).

Dozens of Indigenous nations have launched programs to teach their languages, but more urgent efforts are needed to train fluent speakers before it’s too late. AIHEC is aware of 35 Native American languages that are being taught to children across the country and 33 tribal colleges offered Native language courses as of 2022.

In many places, a race is on to compile language material into databases and make new dictionaries before the situation worsens.

“It cannot wait for five years. It cannot wait for another 10 years. This needs to happen right now,” said Dr. Jurgita Antoine, an applied linguist and deputy director for Native American Language Research at AIHEC. “We need to work with the elders and try to learn from them as much as we can.”

Passed-down dream from a father

The U.S. government has admitted that it purposefully tried to abolish these languages for many years.

For instance, between 1819 and 1969, the United States established or supported a total of 408 boarding schools across 37 states (or then-territories), including Alaska and Hawaii, with the objective to “civilize” and “assimilate” American Indians, according to an investigation by the Interior Department, released in May 2022. Boarding schools forced students to stop speaking their native languages and go by English names.

The federal government now wants to begin the “healing process.”

“This reorientation of Federal policy is necessary to counteract nearly two centuries of Federal policies aimed at the destruction of Tribal languages and cultures,” said Bryan Newland, assistant secretary of Indian Affairs said in a letter to Interior Secretary Deborah Haaland, the first Native American to hold the position.

In a 2024 fiscal year budget request, the Bureau of Indian Affairs doubled its funding request for Native language revitalization to $50.7 million. More specifically, the budget set apart $7.5 million for Native language immersion programs in Bureau of Indian Education funded schools “that will lead to Native language oral proficiency.”

In Cherokee, Catcuce Tiger saw the impact of that effort to destroy Native languages in his family history. All four of his grandparents were sent to a boarding school.

“So my parents and myself, we’re products of that.” said Tiger, a Cherokee language teacher at Cherokee Central School. Tiger said although most families do have first-language speakers of tribal languages in their family, they don’t grow up with the language.

Similar to Dawn Arneach, Tiger grew up far from Cherokee and his tribe, in Nashville, Tennessee. After college, he decided to move to North Carolina to live around his family among the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians as an adult.

Tiger said that Cherokee language always had an indescribable attraction that pulled him to the home of his ancestors. Whenever Tiger heard someone in his family speak Cherokee, he felt intrigued by its inherent beauty. In high school, Tiger told his mom that he was interested in Cherokee, and he received a Cherokee language CD from her as a Christmas gift. That’s when he began to build the blocks of his linguistic education, starting with basic nouns and verbs.

Fifteen years since he first started learning the language, Tiger now speaks fluently. He said that he and his wife emphasize language and cultural identity when raising their boys, now nine and six.

“That's something that I wanted for them that I wasn't able to have for myself,” Tiger said.

At school, Cherokee ‘is who we are’

Tiger’s children attend the New Kituwah Academy Elementary, which offers Cherokee language and cultural values.

From kindergarten to second grade at the school, students speak exclusively in Cherokee throughout the day, with the exception of a half-hour English session. Starting from third grade, students have half of the day in English and half of the day in Cherokee until their graduation. This approach aims to equip students with proficiency in both languages as they advance to middle school.

Arneach’s son French, who has taught at New Kituwah for more than six years, said he wants pupils to speak the Cherokee language from the moment they step into the classroom. He greets them outside the classroom by reminding them to introduce themselves in Cherokee, and ask "ᏙᎢᏳᏍᏗ ᎯᏬᏂᎮᏍᏗ?" , which translates to "What are you going to speak?"

French infuses the classroom with an element of fun by acting goofy to engage students in Cherokee instead of English. With his playful approach, French intends to convey to his students that making mistakes while learning the language is not only acceptable, but also a natural part of the process.

“When they're little kids, I don't want to put pressure on them that they need to learn it immediately. I just want them to relax and have fun with it,” French said. As kids progress through the school, they gradually develop a deeper understanding of the language's significance, he added.

New Kituwah Academy opened in 2004 as a daycare with only one classroom of babies. Growing alongside these young ones, New Kituwah moved into a renovated motel in 2009, and expanded to establish a kindergarten and an elementary school. In 2022, the very first cohort of students — those babies from 2004 — celebrated their high school graduation. While the majority of these graduates attended college, a few returned to work at New Kituwah to help develop curriculum.

Kylie Shuler, the manager of New Kituwah Academy Elementary, said kids at the academy grow up like a family because they move up in grades together in the same small group. There are also strong connections between students and 35 staff in early childhood and elementary departments.

Although many schools across the country teach students a little about Native American culture and history, New Kituwah teaches Cherokee culture every day, Shuler said.

“It's just who we are,” Shuler said. “We teach that being Cherokee means to be good, be kind-hearted, be a good citizen, be kind to the elders.”

The majority of school funding comes from the Harrah's Cherokee Casino Resort, which is a ten-minute drive from the school. The school also receives federal funding, including from the Esther Martinez Language Grant, for supplements like curriculum development and technology. Thanks to the grants, parents only pay for the daycare. The elementary school is free.

“We are very fortunate in that aspect of having funding,” Shuler said.

But what they really need is teachers. She feels a sense of urgency because the average age of Native speakers is over 70.

“Our issue is our non-renewable resource — we need to have speakers,” Shuler said. “You can't give me an amount of money to buy me a speaker.”

The school lost four fluent Cherokee teachers in 2016 when the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians offered a buyout for people who were near retirement age. Now, most teachers are still perfecting their language skills, and take classes four days a week.

The tribe encourages adults to become fluent, as adult language programs are important in fostering more educators capable of cultivating a new generation of Cherokee speakers. Currently, the tribe pays adult students full-time salaries to study Cherokee for two years. In exchange, they commit to becoming full-time teachers at New Kituwah upon completion.

Curriculum made in-house

Another challenge the school faces is that it needs to create its own teaching materials, and the school is working on it. New Kituwah has a curriculum department to design classes and translate English textbooks into Cherokee in subjects like math and social studies, following the world language standards of North Carolina Department of Public Instruction.

“There's no textbook. You can't go and buy it off of McGraw Hill or anything like that. We have to make everything in house.” Shuler said, referring to a popular publishing house.

New Kituwah is also working with the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma to share resources, such as language books, videos and cartoons. However, they also need to adapt the resources because they speak different dialects.

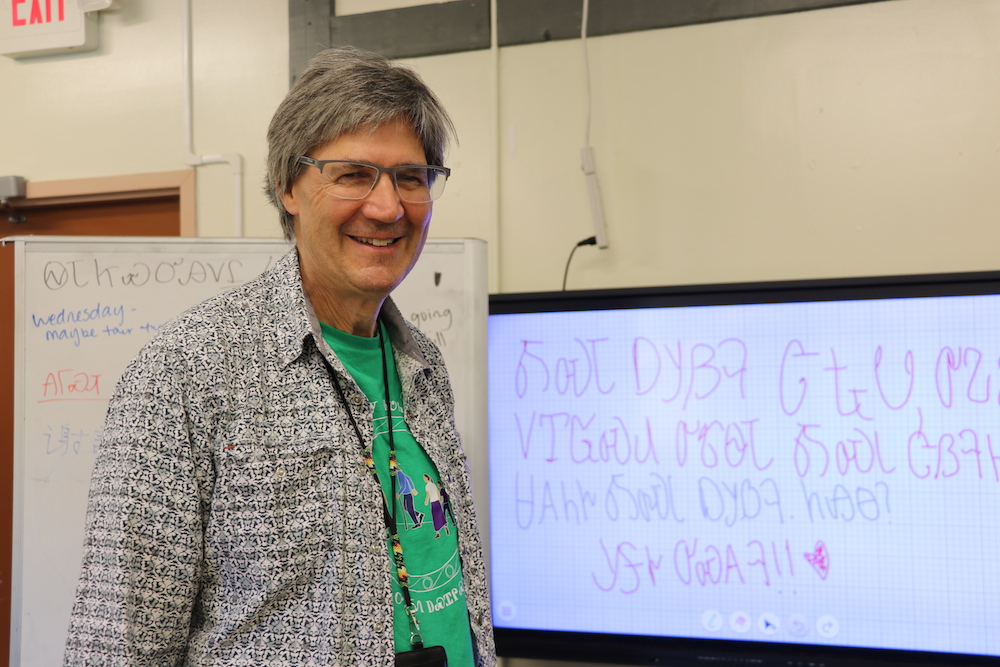

Hartwell Francis is one of two linguists who work as curriculum developers in New Kituwah Academy Elementary.

Earlier in his career, he taught English in Mexico and Japan and became interested in linguistics. He later earned a degree in theoretical linguistics. Although he didn’t know any Cherokee, Francis got a job as the director of the Cherokee language program at Western Carolina University in 2006. Since then, he dedicated himself to learning the language and helping revitalize it.

In 2021, Francis was admitted as an honorary member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indian for “his work in preserving the Cherokee language”, after “a decade getting to know the speakers and working with almost every language program in Cherokee”, according to Cherokee One Feather, a local newspaper.

Francis has a Cherokee name that means “white rabbit” in English. He said a Cherokee friend gave him this name. It stems from a name the Cherokees gave a friendly European settler a long time ago.

Francis said he used the state standards for teaching foreign languages as he developed the curriculum for grades one through six. Francis structured lessons with carefully planned activities that are amusing and also educational.

As an education curriculum designer, Francis wishes he could offer teachers a vast array of materials in Cherokee, so they could be more creative and flexible in their teaching. But the language hasn’t been widely documented in recordings or written materials.

“You have the whole internet that's all English language, and you can go on there and cruise around, ” Francis said. “That doesn't exist in Native American languages.”

French said it would be helpful to have more cartoons, movies, and even billboards in Cherokee language to show the kids that “it's not just a school thing, it's everywhere.”

Across the country, tribal colleges and universities are stepping up efforts to revive Indigenous languages. They started offering online courses, which provide opportunities to learn Indigenous languages, even for Indigenous people who live far from reservations. The enrollment in these courses has doubled or tripled compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic enrollment, according to Carrie Billy, the president of American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

“I'm a big supporter of making it online,” Billy said. “I live here in the DC area, so it's not as accessible for me as it is for people who are actually still living on the reservation.”

Presenting the language to a bigger world

Nine-year-old Catcuce Micco Tiger has the same first name as his father. He’s in fourth grade at New Kituwah Academy. He likes playing baseball and riding his bike around his house on the top of a mountain near Cherokee.

Last Christmas, Catcuce lit the US Capitol Christmas Tree alongside former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other lawmakers in Washington D.C. His essay about preserving his tribe's culture in a contest helped him earn this opportunity. At the ceremony, Catcuce kicked off the speech by saying in Cherokee, “ᏏᏲ ᏂᎦᏓ, ᎣᏣᎵᎮᎵᎦ ᏥᏤᏙᎭ”, which means, “Hello everyone, we are all happy to be here.” Catcuce then told the Cherokee legend of evergreen trees.

Catcuce’s father Tiger said it was a monumental event in Catcuce’s life. He and his wife are proud of his son, as Catcuce not only shined on the stage but also highlighted his family and community.

Tiger hopes his kids will have the best possibilities in the future and go out to see a bigger world, but he also wishes they will continue their language journey. He wants them to take pride in their language and share it with other people. That’s how Tiger believes the language will survive.

“I like to think that if something happened [and] I wasn't around anymore that they would continue to want to learn and be supported by their family and their community to learn, since they've been in the language since they were tiny, tiny babies,” Tiger said.

Lynn Yunfei Liu is a Medill News Service reporter and graduate student at Northwestern focusing on business, finance and global markets. Pingping Yin is a graduate student at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism in the Politics, Policy and Foreign Affairs program. Both are based in Washington, D.C.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher