Special to Native News Online, this is the first in a series from journalist Jenni Monet (K’awaika) looking at the issue of Carlisle Indian Boarding School’s Outing Project. You can follow her work here and at Indigenously.org

In June, the Biden Administration announced it was launching an investigation into the agonizing legacy of Indian boarding schools in America. Journalist Jenni Monet (K'awaika) plotted a multistate investigation of her own, tracing the steps of her great-grandfather, whose bonds to the Carlisle Indian Boarding School in Pennsylvania and its Outing Program have stayed with her family for generations.

Advisory: This article contains images, names, and references to deceased persons including other information that may trigger secondary trauma or PTSD. We encourage individuals to seek counseling or healing if you experience any stress related to boarding school history.

Louellyn White responded with apprehension in the first email exchanges we shared. It was the kind of caution I know well from my years of reporting in Indian Country — a sussing out and a testing of trust. I took no offense.

Louellyn is Mohawk from Akwesasne in the Mohawk Valley of central New York State. She’s a professor in the First Peoples Studies program at Concordia University in Montreal, but that hardly means she’s disengaged with United States-based Indigenous affairs. “To be very candid, upfront, I want to know who you’ve spoken to already,” she asked when I approached her about the Carlisle Indian Boarding School. “I’m careful who I work with,” she added in a subsequent email.

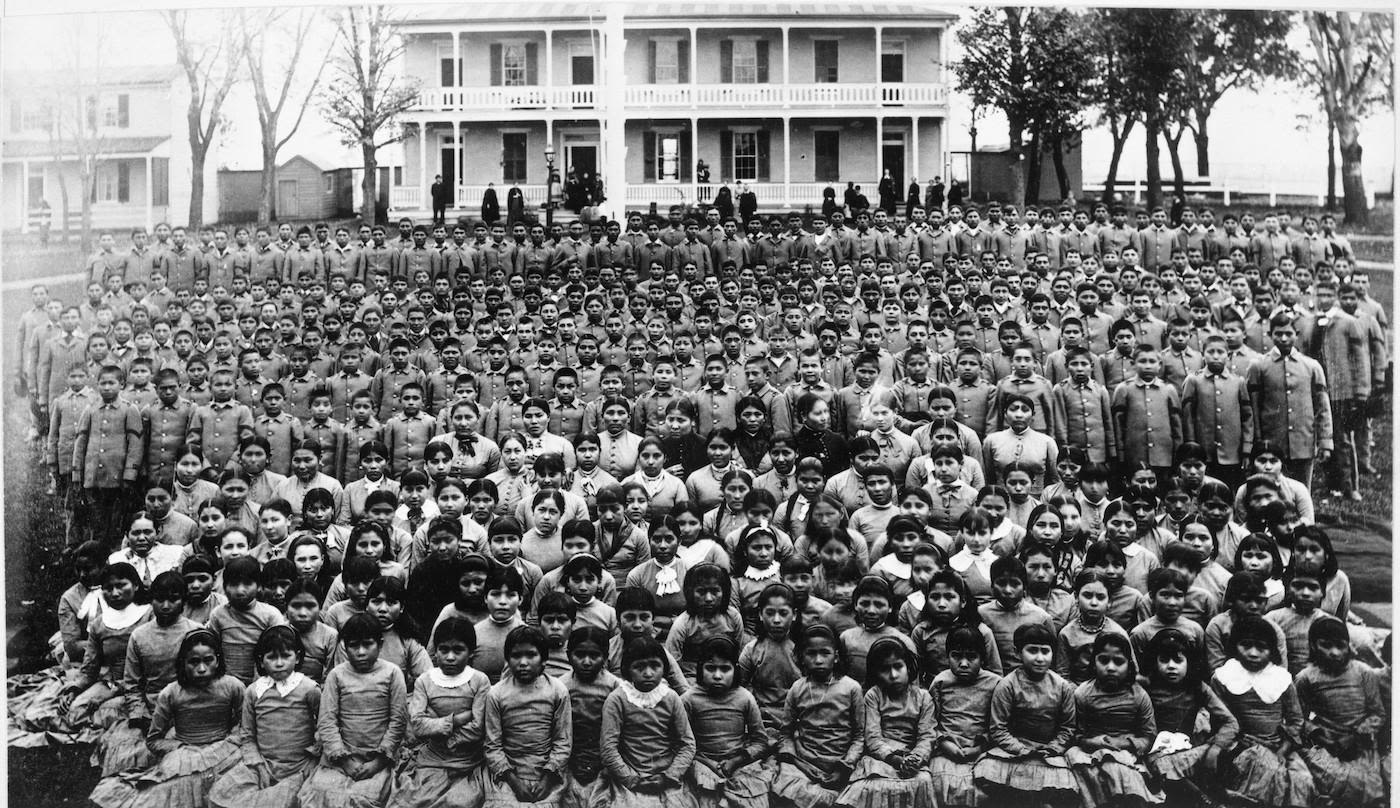

The former Carlisle Indian Industrial Boarding School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania is today part of the United States Army War College. At five each evening, bugles ring out across a campus that looks very much like it did more than a century ago. That’s when thousands of Native American and Alaska Native youth passed through these former Army barracks—as students. Established as the nation’s first federal off-reservation boarding school by a government determined to solve “the Indian Problem,” the methods here initiated militarized cultural genocide on Natives who were shorn of their braids, their names, their languages, and their traditions. The most egregious cases ended in loss of life.

Louellyn’s Mohawk grandfather and other relatives are former students at Carlisle. Across two decades, she has made researching the student experience there a centerpiece of her scholarship. And she was generous in sharing her knowledge with me upon learning about my upcoming reporting trip to Pennsylvania, tracing my great-grandfather’s journey from the boarding school back to our homelands, Laguna Pueblo (Kawaik'a) in New Mexico.

Who have I spoken to? I nodded to myself, recognizing Louellyn’s reluctance, a familiar dread whenever our traumas, our histories, and our identities are too-often targeted for narrative extraction and exploitation. My talks with the professor also generated a deep sense of care and responsibility in approaching this work — reporting that demands sensitivity (anticipating emotional afflictions which may be invisible); accuracy (resisting facile throughlines about a complex legacy); and a willingness to face bigotry (when I told a colleague about my assignment, she responded that parts of Pennsylvania, where I was headed, could be considered “Trump country”).

“Bigger picture. More perspective,” Louellyn told me. “That can only help tell this story.”

Uprooted lives, stolen identities, disappearances, and deaths: this story is one that has been waiting for attention—and for a really long time. Twenty-seven miles north of Gettysburg lies the Carlisle school cemetery where rows of white marble headstones mark the remains of students who died from disease, displacement, and discrimination. In the last five years, the bodies of 22 children have been repatriated to families across Indian Country. A recent homecoming was of an Aleut girl named Sophia Tetoff (misspelled as “Sophia Tatoff”), and whose Indigenous nationality was listed as “Chuskon,” which either was made up or mangled by school administrators; there is no such thing as a “Chuskon” tribe.

Ever since Interior Secretary Carl Schurz approved the boarding school in 1879, the exposure it has received has been woefully one-sided: a saga of westward expansion by valiant settlers, as spun by policymakers and power brokers heroizing their role in "extinguishing" Indigenous title to the land. More than a century of miseducation in America has kept the complete history obscured. Except it’s not just history to the thousands of Natives who live with this legacy — good, bad, or otherwise. Across Indian Country, mention boarding schools (as many as 366 were opened in the U.S. after Carlisle) and you’ll receive different opinions, most of them somber, but others more pragmatic, like the story of my great-grandfather.

It depends.

"Pupils of this school" Carlisle Indian Training School, 1885. Image: Courtesy of Repository: National Archives and Records Administration

The recent surge in interest around Indian boarding schools in America began after 215 bodies believed to be of Native students were detected by ground radar technology on the campus of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada in late May. The words “shocking” and “disbelief” were widely used by outsiders learning about these schools for the first time. But in Indian Country on both sides of the colonial border, it’s a history that has in many ways defined us, even when it has been discounted for decades.

“It’s something we’ve always had to fight to prove,” said Roseanne Casimir Kukpi7 (Chief) of the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc First Nation in British Columbia. “It’s basically been denied by government.” The residential school was situated on Tk’emlups land.

Soon after the bodies were detected, Chief Casimir held an online press conference where she reminded reporters that Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission had recommended an investigation of Kamloops in 2015, a radar sweep that never came. Eventually, she realized it would require the First Nations community to take on the work itself. So it did.

That same year, in 2015, Martha Small (Northern Cheyenne) had just completed her graduate thesis for Montana State University. It revealed a near-identical discovery: a swath of unmarked graves at the Chemawa Indian School near Salem, Oregon. She matched the unidentified electronic readings with more than 200 student graves at a cemetery already there. Her research received little notice, but one group who believed her was the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

Today, the Coalition, which goes by the acronym NABS, is inundated with requests from the media and special-interest groups. But back in 2015, it was like Casimir and Small: largely ignored. The shift in societal acceptance for their heartwork has everything to do with fresh criticism over how the colonization of North America has been misconstrued—driven by new evidence and an emergence of progressive moral imperatives.

My interest in this timeline is obviously personal. Raised in part on Laguna Pueblo by my elders, I grew up aware of details that took me years to understand: for instance, why my great-grandma, Helen, latched onto the Bible with outsized devotion, or reasons why her daughter, my Grandma June, was bullied for the way she spoke our Native language, Keres. One thing that always flummoxed me, though, was why subcommunities across our pueblo in New Mexico were marked with East Coast names — New York, Harrisburg, Chinatown, or the name of our own family plot, Philadelphia.

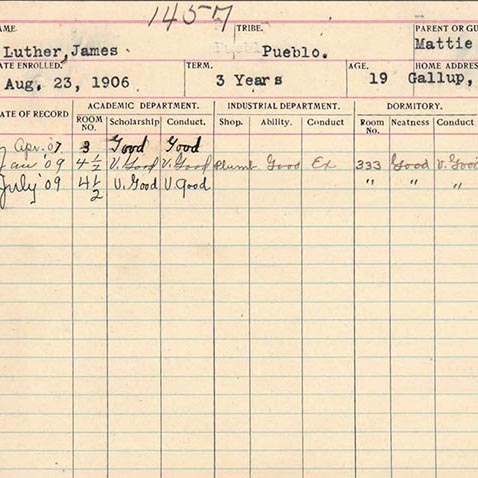

In the background was always the memory of my great-grandfather, James Reid Luther.

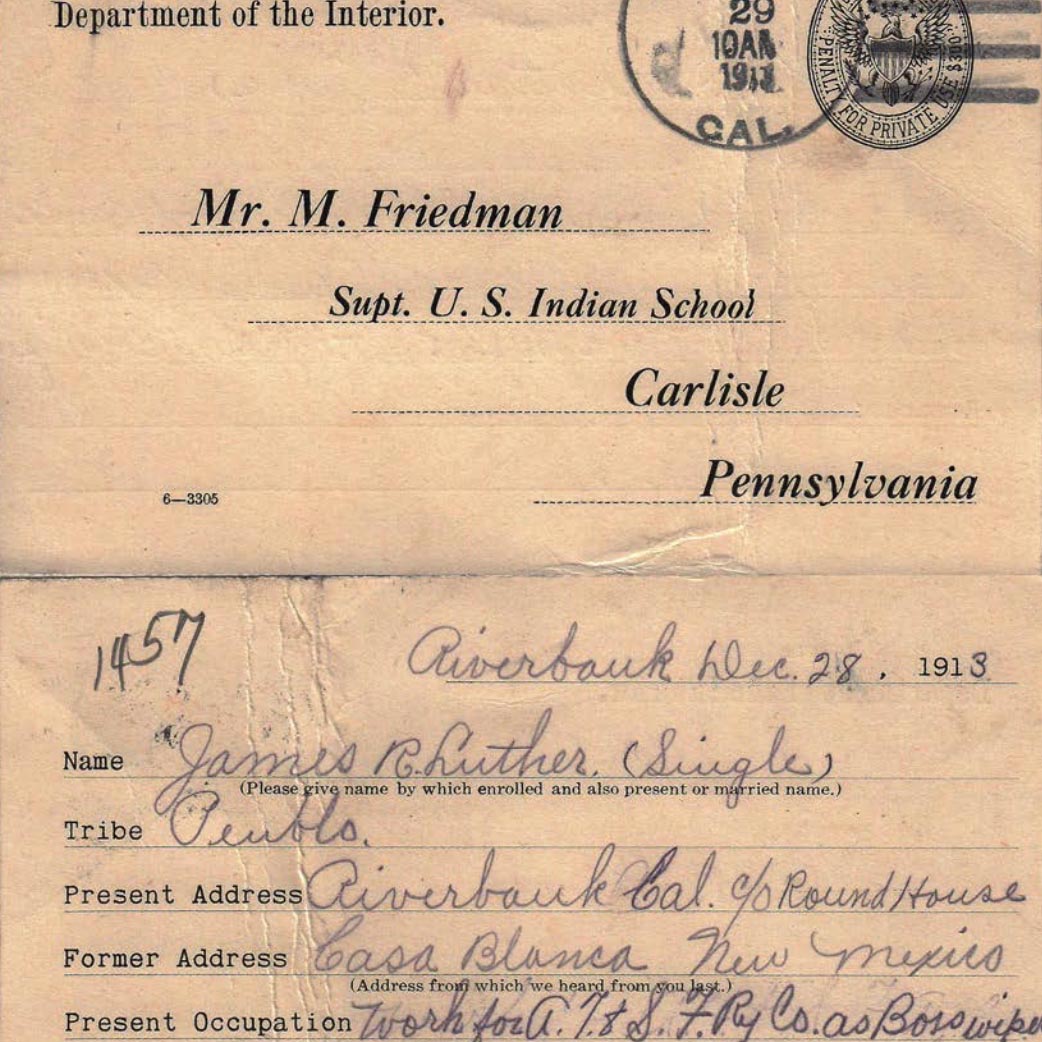

Nicknamed “Jas,” James was a railyard worker-turned-rancher from Casa Blanca, a village within a village on Laguna Pueblo. When he embarked to cities like San Francisco, he’d sit for portraits wearing a weighty gaze, a pressed suit, and polished wingtips tied with ribbon laces. But he had a jocular side. In other photo shoots, he’d dress in exaggerated western wear — tiny cowboy hats contrasted with large feathery chaps. He’d print these photos into postcards and send them to the woman he’d eventually marry, my great-grandmother, Helen Daylia (later, Dailey). The two married in Albuquerque on a September day in 1915 and grew a family: two sons and three daughters. To say the namesake of their firstborn, Raymond, is symbolic — in telling this family legacy — it’s more than an understatement.

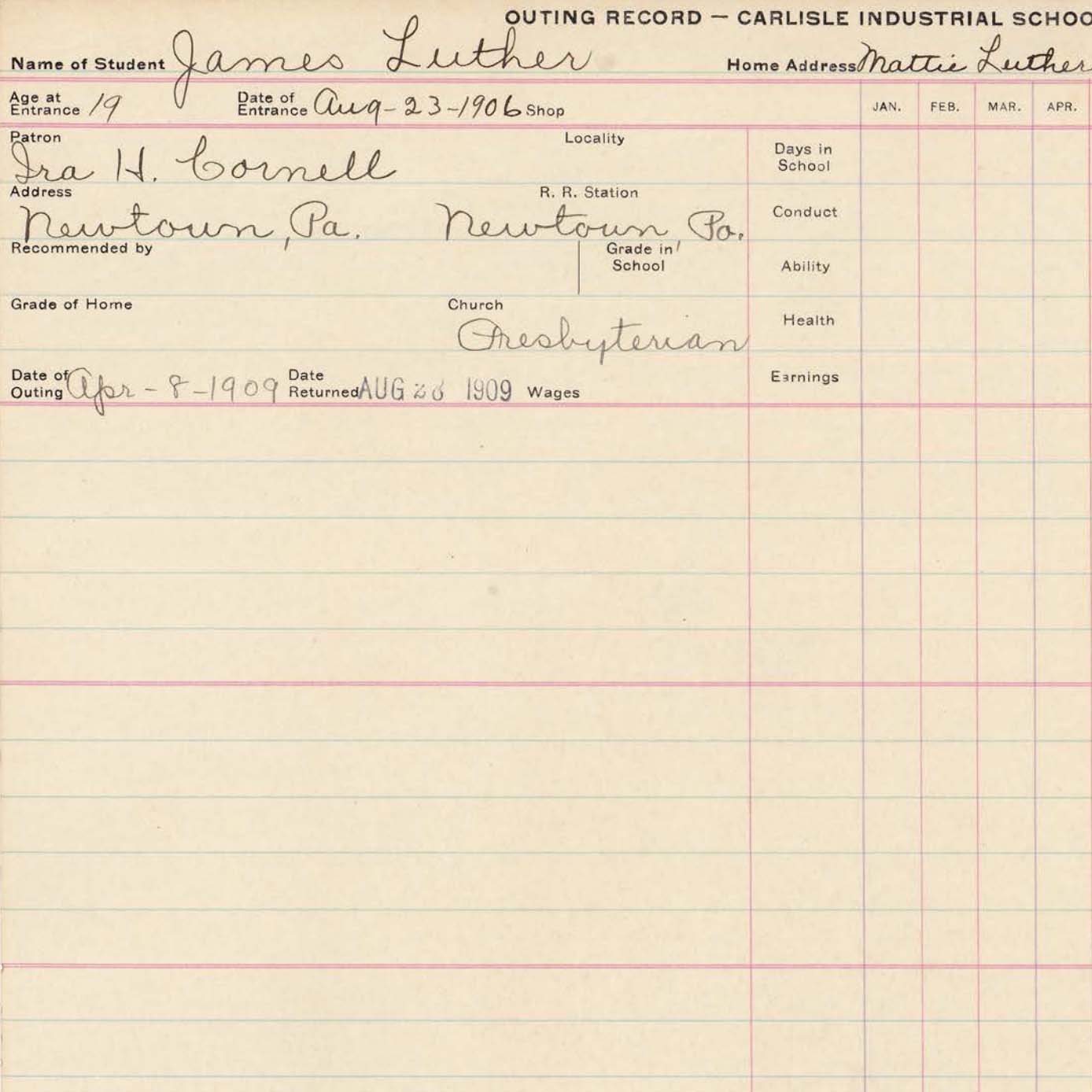

Carlisle School records trace my great-grandfather’s student experience to a family farm in Newtown, in Bucks County, about 130 miles east of Carlisle. There, he bonded like brothers with a boy named Raymond Cornell, the son of the man who hired James as a low-wage laborer during the summer of 1909. The arrangement was part of the Carlisle Outing Program, a name that comes across as gleeful as a garden party. But the Native students placed in these white people’s homes often experienced hardship. Girls worked as housekeepers; boys as farmhands. Many of those children reported abuse. Some died while on Outing; others disappeared. But my great-grandfather, an eager man in his early 20s, befriended a boy who, decades later, would turn up at our Pueblo doorstep — a man that my family would come to regard as "Uncle Raymond."

Sentiments are rare in the trail of documents that James left behind (he died before I was born), including the progress reports he sent back to Carlisle, and the letters and notebooks chronicling his life with Helen. But what does come through, as complicated as it may be, is an obvious acceptance of all that Carlisle promoted — “to kill the Indian, and save the man” — even when, perhaps by chance, such a mission had failed.

I was intent on making sense out of it.

The Spirit of Transportation relief sculpture at 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, representing a procession of "progress" by Karl Bitter, 1895 (Jenni Monet, Oct. 10, 2021)

Over the course of ten days in October, I went to Pennsylvania in search of answers about my great-grandfather’s legacy from Carlisle. It’s a journey that earns Louellyn’s concern about narrative disruption which smacks squarely with research that she and many others have unpacked long before me—about the Outing Program.

A vocational project, Outings were backed by Quakers and Presbyterians, in which as many as 5,000 students were assigned to their homes throughout the East Coast. Some were like my great-grandfather and sent on multiple Outings, according to a deep cache of records kept by the school, the government, and newspapers nationwide.

In my reporter's notebook, there are details from speaking with some of the last living Pennsylvanians (people in their eighties and nineties) who hold shreds of information so valuable to this complex history. There are also notes I jotted down from conversations with my own relatives, including personal reflections from when some of those talks grew tense. And there are takeaways from Laguna archivists and knowledge-keepers who helped me make lesser-known connections between Laguna and Carlisle. I hope that what I’ve uncovered here will be tender enough for my relatives and extended kin to receive and share — with their families, their colleagues, and their individual communities.

The objective of my reporting was to drop below politics: to explore and understand more deeply an unfinished story of memory and its modern impact. Even better, to drop below victimization, below exploitation, and to connect with my great-grandfather’s past as an act of reclaiming all that Carlisle tried to steal.