- Details

- By Native American Rights Funds (NARF)

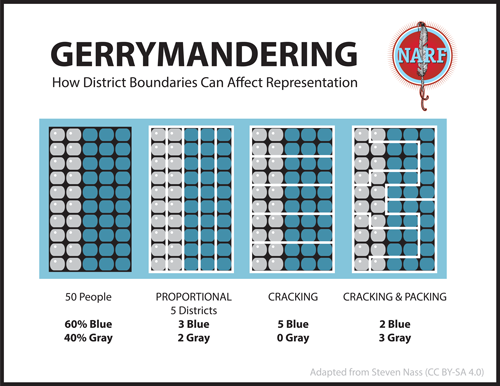

Every ten years, states redraw the community lines for both Native and non-Native lands within their borders. This process is known as redistricting. These imaginary lines determine election districts, and the way that they are drawn can have a huge impact on the people that live in a community.

For example, imagine if a community district line is drawn through the center of a reservation or tribe. That line separates the Native community and tribal voters into two smaller groups. The voices of those groups can much more easily be overwhelmed by surrounding non-Native communities. It is easy to picture how that line would affect the tribe’s voting power, voice, and access to resources.  If redistricting is not done fairly, it can affect a tribe’s voting power, voice, and access to resources. (Graphic/NARF)

If redistricting is not done fairly, it can affect a tribe’s voting power, voice, and access to resources. (Graphic/NARF)

You may already know, but the redistricting season is here. Right now, states are drafting the maps that they will use for the next decade, and Native communities must take action to ensure that people who may know nothing about us are not drawing lines without our input. What we do now will have long-ranging effects. A fair district map is a first step in combating centuries of sustained, systemic racism. The decisions made (whether good or bad) will directly influence our lives for the next ten years.

Although “redistricting” may sound like a process that is happening far away and has nothing to do with us, it is not. Identifying community district boundaries is a very local action that has long-reaching impacts. Those imaginary district lines help determine who will represent us and what resources we will get—resources like funding for schools, roads, libraries, and hospitals. When we come together and fight for a fair district map, we are fighting for our community and our future.

This is why it is so important for us to join and advocate for our communities during the redistricting process. Achieving fair districting in Indian Country for the next ten years requires community action right now! The lines are being drawn, and we need to make sure that our communities are fairly represented. We must take action for our future and our children’s future.

This process is already underway. In places like Alaska, they have already released draft maps and are seeking citizen feedback. In other states, like Montana, they will be holding hearings throughout October, November, and December. Although the process is different in each state, the actions that we can take are clear. We must:

- Organize our communities. Come together with others on our reservation, in our tribe, or in neighboring communities to combine efforts and voices. Across the country, local communities, Native and non-Native, are organizing and advocating for more fair district boundary lines.

- Define the boundaries that we want and need. We know our communities best, and we are best able to identify accurate community district lines.

- Communicate to the people who are drawing the lines what boundaries are appropriate for our community and why. Not only do we know our communities, we need to share that information so that outside voices aren’t defining us. This advocacy can include speaking at public hearings and submitting written testimony.

This redistricting process is happening in communities across the country right now. To help Native communities and tribes organize, the Native American Rights Fund is providing free guides and tools at https://vote.narf.org/redistricting/. We must participate and #ShapeNativeFutures by coming together and advocating for ourselves and our neighbors, our children, and our futures.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher