- Details

- By Professor Victoria Sutton

Guest Opinion. “Book bans” prevent access to ideas based on content and are thus unconstitutional. Books can "have limited access based on some constitutional exceptions, notably obscenity and pornography can be banned from access by children, for example. Another example is time, place and manner but this would be based only on the hours set for the library to be open, for example, and cannot be based on content.

In October 2024, in a county just north of Houston, Montgomery County — a citizen’s advisory committee made the decision to reclassify a non-fiction book written from a Native American perspective about their own tribe to the fiction section of the library.

So reclassifying a book as fiction, when it is non-fiction, is making a statement about the book; but if it is not limiting access or banning the book, then it is not an unconstitutional violation of the Free Speech clause of the First Amendment. In fact, the free expression of the library (or its advisory committee) in its classification of the book is protected by the First Amendment.

Does Montgomery County include Aboriginal land?

The U.S. Court of Claims says it does.

Montgomery County, Texas is a bustling suburban county next to Harris County, Texas where the fourth largest city in America sits (Houston). One of the three federally recognized tribes in Texas, the Alabama Coushatta Nation, is located only 65 miles away. However, the U.S. Federal Circuit (I once worked for Judge Plager there as a law student) recommended that the U.S. pay the Alabama Coushatta $270.6 million for land that is still legally theirs. In Alabama–Coushatta Tribe of Tex. v. United States, No. 3–83, 2000 WL 1013532 (Fed.Cl. June 19, 2000), the Court of Federal Claims made a nonbinding recommendation to Congress that the federal government “violated its fiduciary obligations by knowingly failing to protect 2,850,028 acres of the Tribe's aboriginal lands” and damages were due. It was determined that the land was aboriginal land (never ceded to the U.S.) and to which the tribe possesses and can occupy. This covers an eleven county area and a big section of Montgomery County. The Alabama Coushatta Nation has sought to enforce this judgment.

Whether this land dispute with the Alabama Coushatta contributed to the reclassification of a book about the impacts of colonization on a Native Nation including the taking of their land into a “fiction” section, is not clear.

The book

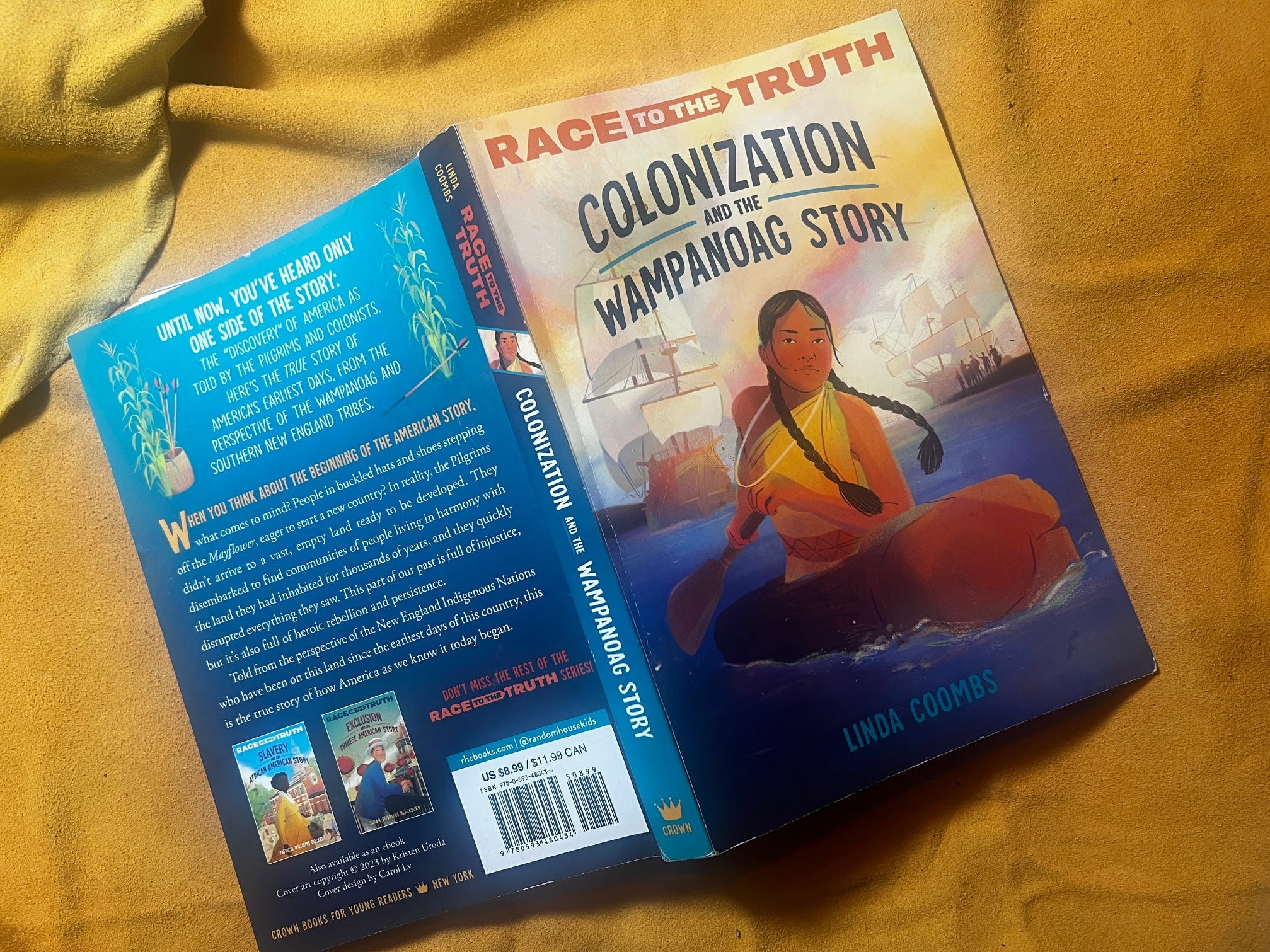

The book, “Colonization and the Wampanoag Story” by Linda Coombs (Aquinnah Wampanoag), published by Crown Books for Young Readers, NY (2023), tells the story of the Wampanoag Tribe’s pre-contact and contact experiences, told by a citizen of the Wampanoag Tribe. For context, the Wampanoag Tribe is the Native Nation responsible for helping the Pilgrims survive the winter by supplying them with food and knowledge and are the Native Americans portrayed in the story of the first Thanksgiving. (I wrote about another current legal controversy with the Wampanoag Nation.)

The book has won a number of awards, and is notably mentioned on the blog that promotes children’s literature in the area of Native American studies. The title was the official selection by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for the Library of Congress’ 2024 Great Reads for Kids, and was a finalist in the middle-grade category for the New England Independent Booksellers Association’s book awards.

I read the book, and while I might have written about the Doctrine of Discovery differently, her viewpoint is not wrong, and it is her perspective about how the Doctrine of Discovery impacted and continues to impact her Tribe. I particularly liked her approach to writing about pre-colonial life as stories that included children.

Coombs’s Chapter Ten is particularly helpful to any reader as she walks through traditional Wampanoag law and philosophy of law, leading to the imposition of laws by the Massachusetts Bay Colony a mere 40 years after they arrived and took the land that belonged to the Wampanoag Nation. She gives a short description of these laws and the impact that they had on the indigenous people. Laws that prohibited traditional ceremonies of the Wampanoag Nation set in motion centuries of these laws that followed, and it is important to see how they started here in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

The back cover of the book mentions this book is “the true story of America's earliest days, from the perspective of the Wampanoag . . .”. and further, “ . . . this is the true story of how America as we know it today began.”

Reversal of the reclassification

A list of free expression advocacy organizations wrote to the Montgomery County Executive Committee:

Colonization and the Wampanoag Story is a carefully researched, fact-based account of the Indigenous perspective of the tribes of the New England area on the impacts of European colonization. Moving it to the fiction section communicates distrust of material that reflects the truths of our American history. It diminishes the legitimacy of Coombs's perspective as a member of the Wampanoag Tribe and Indigenous educators who recommend its use.

We ask the Commission to overturn the Review Committee’s decision on Colonization and the Wampanoag Story and order it to stay in the Juvenile Nonfiction Collection across your county’s public libraries.

October 22, 2024, the Montgomery County Commission reversed the re-classification of the book and it is back on the shelf as a non-fiction book.

Native American Education

There is an effort to include more education about one of the three sovereign governments in America — Native Nations. That effort is also underway in Texas.

A petition to include a course on Native American Studies for public schools has been circulated and the group is seeking to make a course in Native American Studies a permanent elective course.

Avoiding the Book Ban

The act of banning books and removing them from the shelf, even for a short time, is likely to be an unconstitutional burden on First Amendment, Free Expression. The result of book banning cases has been based on a test that looks at the motivation of the book banner — was the motive a viewpoint motive or was it because the book was factually incorrect? In a case in Miami, a book about Cuban life was deemed factually incorrect by someone who was a political prisoner in Cuba, and upon examination it was agreed that it was factually incorrect, applying the Pico test finding the Board was motivated by its factual inaccuracy rather than a viewpoint. Whereas in a case involving the removal of a book called Voodoo & Hoodoo, which included various “spells” in Voodoo that the parent did not want their child to read, the court found this was unconstitutional viewpoint exclusion.

So by simply re-classifying the book as “fiction” the issue of book banning was avoided which would have required an examination of the motive of the governmental body effecting the ban. In this case, there was no reason given. The removal of the book while they made their decision no matter how short the time was a deprivation of a civil right; however, the re-classification of the book as “fiction” was a creative reinvention of a “ban”. In the end the County Commission made the right choice and avoided a judicial examination of motive.

To read more articles by Professor Sutton go to: https://profvictoria.substack.

Professor Victoria Sutton (Lumbee) is a law professor on the faculty of Texas Tech University. In 2005, Sutton became a founding member of the National Congress of American Indians, Policy Advisory Board to the NCAI Policy Center, positioning the Native American community to act and lead on policy issues affecting Indigenous communities in the United States.

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher