(Graphic: Kaylee VanTuinen, Native News Online)

NINE LITTLE GIRLS

Part 2

As the Charbonneau sisters continued to fight for the right to sue the Catholic Church in South Dakota for Indian boarding school abuses, the 9LittleGirls movement faced setbacks with the sudden passing of three sisters from COVID complications, cancer, and an aneurysm. With the six remaining sisters aging, their children and relatives hope to shoulder the fight for justice. But it’s proving difficult and they need help.

by Jenna Kunze

*TRIGGER WARNING* This story includes accounts of physical, mental, sexual and emotional abuse that survivors experienced in Indian boarding schools. If you do not have the capacity to engage with these stories right now, we encourage you to read them when you feel more supported. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) has a comprehensive list of healing resources available on its website.

Mary Lou Charbonneau-Byron’s great-granddaughter, liked to play dress up in her closet. At 12 years old, the girl emerged one day from her great-grandmother’s bedroom in 2022 with a proud look on her face. The young girl was wearing a sweatshirt that came down to her knees. Across the front was a logo that read: 9LittleGirls.

“Do you know what that means?” the girl’s grandfather, Neil Byron, asked the child when she unveiled her new outfit to her family outside on the porch. She shook her head. “You need to go ask Nanna what ‘9LittleGirls’ means.”

Back inside the house, Mary Lou explained to the 12-year-old that she and her eight sisters had experienced abuse as children at an Indian boarding school in Marty, South Dakota. 9LittleGirls is the name of the organization meant to bring attention to that abuse and to fight for justice.

“I didn’t go into much detail,” Mary Lou told Native News Online in her kitchen in Granite Falls, Washington, in May 2023. “I asked her if she wanted [to know] more and she said, ‘Not now, I’ll wait till later.’”

Mary Lou has her doubts that later will ever come. She's been fighting for justice and resolution for a dozen years. Now, she's getting older, and has lost three of her sisters in the last four years. Her children, nieces, nephews and relatives may be the best hope for justice to ever be served.

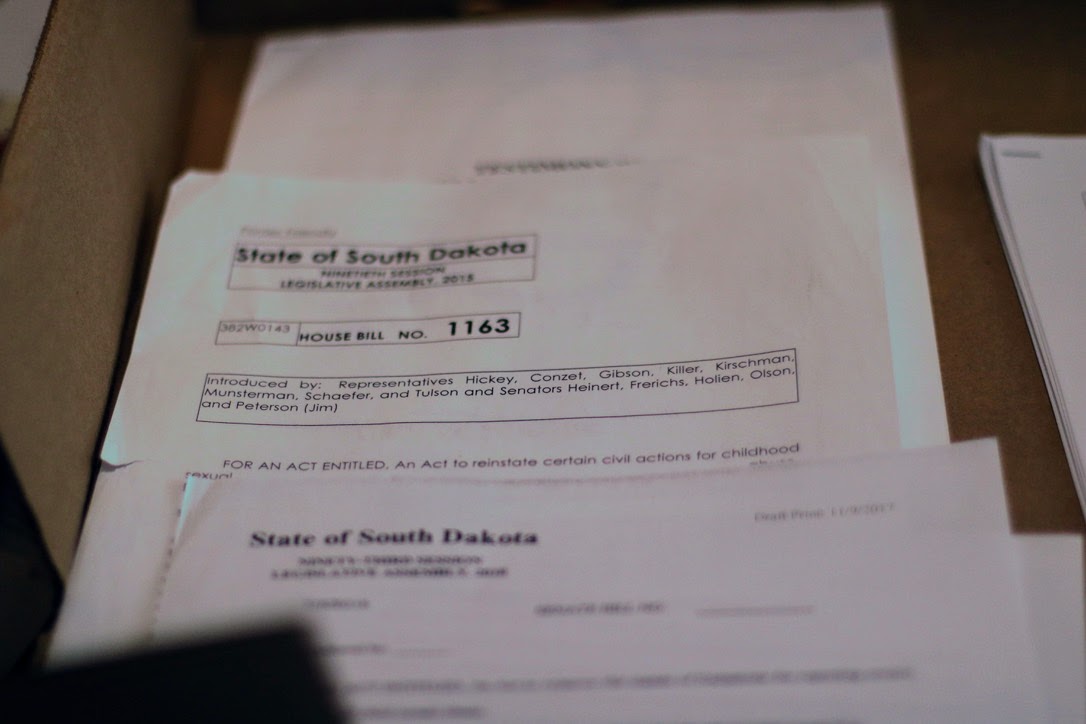

In 2010, days before the lawsuit the Charbonneau sisters had filed against the Catholic Diocese of Sioux Falls and specific priests and nuns they say abused them when they were children in the ‘50s and ‘60s was set to go to trial, the South Dakota Legislature changed the law at the last minute. It narrowed the statute of limitations for child sex-abuse cases. A state circuit-court judge used that revised statute to dismiss the sisters’ lawsuit. That has kept more than 100 Native American survivors of Indian boarding schools, including the nine sisters, from ever bringing their claims to court. Nearly every year since, the nine sisters have set out to change the law, relying on the generations after them for support.

'I WANTED PEOPLE TO REMEMBER THIS WAS ABOUT CHILDREN'

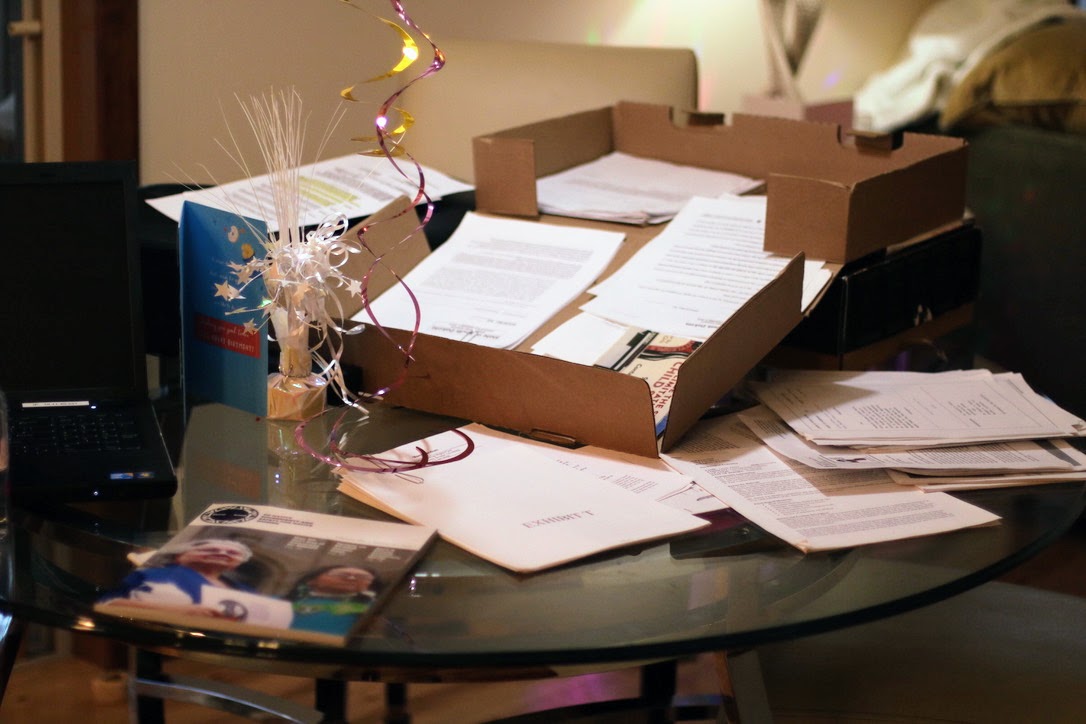

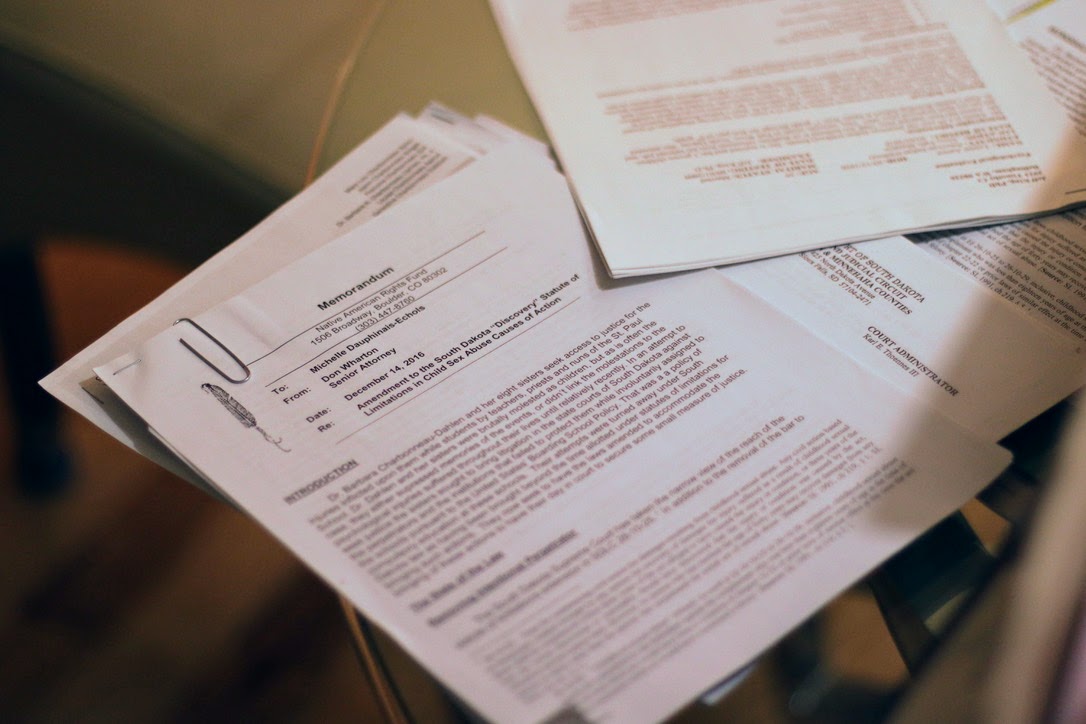

Michelle Dauphinais Echols keeps her years of documents from the battle with the South Dakota lawmakers in an old Roller Derby box, tucked away at her home in Minneapolis.

Nearly every year since 2013, the Charbonneau sisters and other survivors have brought forward legislation to repeal the changes in the statute of limitations, or to create a window to allow them to bring suits even after the statute of limitations had expired. Each year, they’ve been denied justice.

If she’d been born earlier, Dauphinais Echols, 52, could have suffered the same fate as of the nine sisters. She is their second cousin, born a generation behind them on the grounds of the Marty Indian school on the Yankton Sioux Reservation, where her father (the Charbonneau sisters’ cousin) was employed as the school’s director while it was moving from church to tribal control in 1975, four years after Dauphinais Echols was born.

Instead of attending Indian boarding school, Dauphinais Echols went to various tribally run schools on the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indian reservation in Belcourt, North Dakota, where she grew up. She studied at Dartmouth College as an undergraduate, and earned a degree at Georgetown University Law School in 1995, where she was the president of the Native American Law Students Association.

Michelle Dauphinais Echols, pictured at her home in Minneapolis, Minnesota in February 2023. (Photos: Jenna Kunze)

Dauphinais Echols has worked as a corporate attorney for 25 years. So when her cousin, the late Barbara Charbonneau Dahlen, phoned her in 2014 and asked her to be a part of the movement to change the statute of limitations in South Dakota, Dauphinais Echols saw that as an opportunity to fight for justice for a reality she narrowly escaped. Nearly all of the federal Indian boarding schools had closed down or been turned over to tribal control by the 1980s, when Dauphinais Echols was school-aged.

“My whole life, I’ve felt like I had to ‘make it’ so I could help others in my community,” she said from her kitchen table in Minneapolis. On her fridge hung honor-roll certificates her three children earned, and the remnants of birthday decorations celebrating her daughter turning 23 dangled from the light fixtures. “So when Barbara asked if I would be part of it, I was like, ‘Okay, I’m going to give this a try. We’re going to go change the law in South Dakota.’”

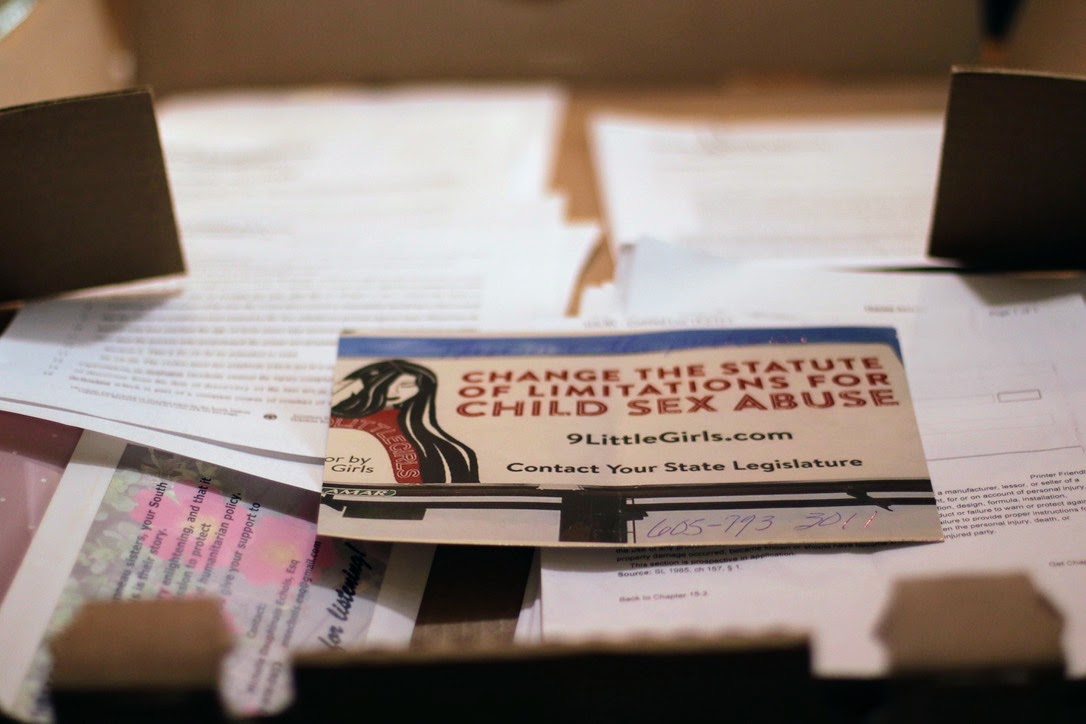

For six years beginning in 2016, Dauphinais Echols drafted legislation that would have restored child-sex-abuse survivors’ opportunity to litigate in court. She created the organization 9LittleGirls to rally support and educate lawmakers and citizens.

“I wanted people to remember this was about children,” Dauphinais Echols said. The group began fundraising and selling T-shirts with their logo, to help offset the expenses of bringing the sisters and supporters to the legislature each year to testify. They developed a presence on social media pages to share their stories, and worked with the Democratic Party to register new voters in the state.

“After the first year, we thought if we could control who was in the legislature, that would help us,” she said. When that didn’t work, they switched their approach. Each year, and with each failure, the women devised a new strategy: they had the bill introduced by members of the state House of Representatives, members of the Senate, Democrats, Republicans, Native legislators, non-Native legislators, and even legislators affiliated with the church.

Even when legislators’ public statements seemed to be in favor of the bill, they voted against it year after year.

At the 2012 House Judiciary Committee hearing to rescind the statute of limitations for any civil cause of action arising out of childhood sexual abuse, Rep. Don Kopp, a Republican from Rapid City, said he was raped as a child, and it took him about four decades to tell anyone about it.

“I'm 69 years old… and when I was young boy of 14, I was raped by several individuals. I was too embarrassed, too ashamed to ever say anything to anybody about it (until I was) about 50 years old, or 55, something like that,” Kopp said. “I finally realized it wasn't my fault that this happened.”

Still, Kopp said he’d vote against the bill.

“The legislatures have heard this story from every angle possible, every point of view possible,” Dauphinais Echols said. “It's not because they're not listening or not hearing. It really is because we're talking about Native people in South Dakota [and it comes down to] racism and protection of the Catholic Church.”

That sentiment was repeated by more than five Native Americans close to the case in South Dakota, plus Matthew Fletcher (Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians), a University of Michigan law professor specializing in Indian law. Fletcher cited a 2013 case in which three Native parents filed a class-action lawsuit alleging that the state of South Dakota was violating the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) by disproportionately removing Native children from their homes and placing them with white families.

“Basically the judges [in Rapid City] said: ‘we're not going to comply with the Indian Child Welfare Act, because your parents are awful people, and there’s nothing you can do to make us stop,’” Fletcher said.

He also mentioned the white Rapid City hotel owner who in 2022 posted on Facebook that she would no longer admit Native American guests, because of a fatal shooting that happened at her hotel between two Native guests.

“That’s South Dakota for you,” Fletcher said. “It’s true of a lot of other places, but definitely South Dakota. This is where the worst Indian Country racism occurs, in towns that are just off the reservation.”

'THEY WANT TO PURSUE THIS, BUT NEED HELP'

In the past three years, the women have stepped back from introducing their annual legislation to regroup. In 2020 and 2021, three of the nine sisters died suddenly, and several other family members — including Barbara Charbonneau’s spouse and one of the sisters’ adult children — also passed.

Dauphinais Echols said the remaining sisters are looking to her to lead them. “They're older women now, and they're dealing with health issues. They want to pursue this, but they need help.”

In the meantime, there has been a national movement for a reckoning with the legacy of Indian boarding schools. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland of the Laguna Pueblo has led an investigation into federal Indian school policies, and the abuse and even death that occurred at federally funded institutions throughout the country, including schools like Marty that were operated by the Catholic Church.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) and Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs Bryan Newland (Bay Mills Indian Community) during the June 2023 “Road to Healing” listening session at the Mille Lacs Community in Minnesota. Haaland and Newland have led the investigation into federal Indian school policies, and the abuse and even death that occurred at federally funded institutions throughout the country, including schools like Marty that were operated by the Catholic Church. (Photo: Darren Thompson for Native News Online)

Last November, Haaland also concluded a 16-month Road to Healing tour, where she collected oral histories from Indian boarding school survivors and their descendants at 12 stops throughout the country. The tour and the larger movement towards a reckoning also brought conversations about intergenerational trauma into the mainstream, including the idea that systemic oppression and abuse of a people can impact an individual's DNA, and that impact can be passed down generations.

Dauphinais Echols herself couldn’t put a word to the way she felt her whole life until recently. The conversation prompted her to recognize her own historical trauma, which has manifested as chronic anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Over her 25 years as a corporate lawyer, Dauphinais Echols has sensed that her heightened levels of anxiety were predestined. She thinks of anxiety levels, or a person’s fight-or-flight mode, as stove dials.

“Normally people are at zero, and then they'll go up with a stressful situation, and then they’ll go back down,” she explained. “Mine seems like it starts out at like an eight or a ten, then I'll get to a high so much more quickly.”

Now, Dauphinais Echols can see how her family’s historical trauma —her great-grandfather, grandparents, and her father all attended Native American boarding schools—both helps and hinders her work.

“I still feel that generational trauma that I'm having to deal with,” she said. “So even though I'm better equipped, I still feel like I need a lot of help.”

Dauphinais Echols isn’t the only relative who feels like she needs help in finally finding justice for the nine little girls.

'I WANT TO FINISH WHAT MY MOTHER - OUR MOTHERS - STARTED'

For several of the Charbonneau sisters’ children, now adults themselves, continuing the fight for their mothers’ justice is a matter of duty to set their mothers free, even in death. But their own intergenerational trauma, mingled with grief over the loss of three of the sisters — their moms and aunties — has made it difficult. Navigating a legal system that wasn’t designed for them has made it even more formidable.

Sarah Sharpe, the 40-year-old daughter of the late Barbara Charbonneau Dahlen, always knew her mother had attended Indian boarding school as a child. She knew that such an experience contributed to her mother’s poor mental health—“episodes,” as she and her siblings called them. Barbara would go into catatonic states of depression, where her eyes would darken and she’d sleep for days.

Sharpe knew her mother got her first menstrual period as a fourth grader—a possible sign of childhood sexual abuse — and that she left boarding school without graduating. Barbara was transferred to North Dakota State Hospital’s psychiatric unit at age 16, an episode recounted in a deposition on April 29, 2009: “B.C.D. recalls an episode where she was taken to the convent and molested and then taken immediately to the state hospital in James Town where she was kept sedated,” it reads.

Sarah Sharpe knew her mom, Barbara Charbonneau Dahlen, attended Indian boarding school as a child and witnessed how the experience contributed to her mother’s poor mental health— “episodes” as she and her siblings called them. (Photo: Courtesy of Sarah Sharpe)

“Mom talked openly about her abuse from when I was young,” Sharpe said, bouncing her one-year-old on her lap during her stepson’s seventh birthday party at an indoor pool in Grand Forks in February 2023. ”But it didn’t really connect with me until I started going to session there [at the legislature]. I knew my mom went through it, I just didn’t know the exact details.”

At a legislative hearing in Pierre, Sharpe learned those details through her mother’s deposition: that she was sexually abused by a priest from ages six to ten. The abuse included “forced oral sex in the stairwell or the little girls’ playroom,” according to the lawsuit.

Barbara Charbonneau became one of the first American Indian in the United States to earn a master’s degree and then Ph.D. in nursing. Her doctoral dissertation topic was “The Impact of Boarding School on American Indians.” (Photo: Courtesy of Sarah Sharpe)

Sharpe also knew that her mother’s experience being called a “dumb Indian” by nuns at school inspired a lifelong pursuit to prove them wrong. In 1994, Barbara Charbonneau became one of the first three American Indians to graduate with a master’s of science degree in nursing from University of North Dakota. Years later, she earned her doctorate from Florida Atlantic University, making her the 15th American Indian in the United States to earn a Ph.D. in nursing. Her dissertation topic was “The Impact of Boarding School on American Indians.”

The Charbonneau sisters defied a lot of the stereotypes that Steve Smith, the attorney defending the church, pushed to the legislators: that they were some “poor Indians seeking handouts.” In particular, Dauphinais Echols said, was Barbara. Barbara’s kids described her as a white-passing PhD who could convince anybody of anything. “If my mom had a second career, she would have been a salesman,” her daughter, Sharp, said. “She could speak to anybody. She would be like ‘Oh you’re a janitor? You work with really disgusting things. Have you ever thought about nursing?”

But still, after more than 30 years of committing her life to increasing public awareness about Indian boarding schools and the intergenerational trauma they left in their wake, Barbara died without even receiving a penny, an apology, or any type of recognition from the religious institution that changed her and her sister’s lives.

“I want to finish what my mother—our mothers—started,” Sharpe said. “It’s about holding institutions accountable.”

AN APOLOGY WOULD MEAN MORE THAN MONEY

Shape’s cousins Neil Byron, 60, and Denise White, 55, told Native News Online that they, too, are committed to carrying forward their mother’s stories, but don’t know where to start.

White traveled with her late mother, Louise, to the legislature twice, and emailed her story “to every news station imaginable” to drum up press. Louise died just before the annual legislative hearing in Pierre in February 2020. She was packing for the trip and, when her husband went to help get her clothes from the bedroom, he found Louise dead of an aneurysm. Her family attributes her death to the trauma she endured at boarding school continuing into her adulthood, revived when she had to try to convince legislators that it had actually happened each year.

Neil Byron, the son of sister Mary Lou Charbonneau-Byron, at his home in Granite Falls, Washington, in May 2023. (Photo: Jenna Kunze)

“The justice system has failed my mother and her sisters and everyone else who was abused at that school and other schools,” White told Native News Online. “Justice would be a day in court to tell the story, to let my mother’s sisters and every victim who wanted to tell their stories [do so]. They need their day in court.”

“An apology would mean more than any money. My soul would be happy if [the church would] just recognize it, instead of trying to just put it underneath the carpet. I’d like to see my mom put it away and close the door… before she passes, but I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

Neil Byron, son of Mary Lou Charbonneau-Byron

For Byron, whose mother’s health has rapidly declined after our meeting last spring (at 80, she’s suffered a series of falls and is currently recovering from a broken back), he wants his mother to find peace in recognition from the Catholic Church while she’s still on earth.

“An apology would mean more than any money,” he said. “My soul would be happy if [the church would] just recognize it, instead of trying to just put it underneath the carpet. I’d like to see my mom put it away and close the door… before she passes, but I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

THEIR JUSTICE WOULD BE MY JUSTICE

Dauphinais Echols—who is in talks with the remaining six sisters to bring legislation forward in 2025, and is helping produce a documentary to build awareness about their story—isn’t holding her breath for the South Dakota legislators to suddenly hear them, though she said she’d love to be surprised.

Instead, she’s pursuing tangible action. She left her corporate attorney gig last year with the hopes to pursue 9LittleGirls full time. She applied for a Bush Foundation grant in 2023 that would have helped pay for her to learn to improve her skills as a public speaker, cultivate a network with other survivor-focused groups to learn from mentors and develop cross-collaboration, and revive cultural practices as a form of self-care. Although she didn’t get that grant, she hopes she’ll land another one.

“If we have enough people that are like-minded, that can sway the opinions of the legislators,” she said. “That’s the bottom line of what I'm trying to do: create awareness. And then from the awareness, we can find like-minded people to further what we're working on. So we could go back and legislate, or we could try something else.”

No matter what, she’s not giving up the fight.

“When I think about it,” she said of her cousins, “Their justice would be my justice.”