- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

WHITECLAY, Neb. — “The Skid Row of the Plains.”

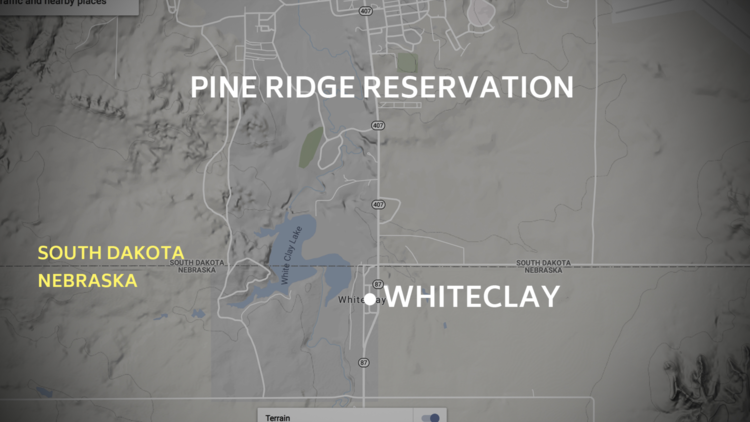

For decades, that painful title aptly described Whiteclay, Neb., a border town that thrived off an exploitation-based economy.

Located two miles from South Dakota’s Oglala Sioux Pine Ridge Reservation, Whiteclay’s only offerings were four cash and carry liquor stores selling 4 million cans of beer annually, primarily to Pine Ridge residents.

“It was like a boulevard of broken dreams. Since the Reservation is dry, there was a lot of outside drinking. It was very visible,” said South Dakota State Senator Red Dawn Foster (Oglala Sioux). “It set the tone of what you‘re expecting the lives of the people on the Reservation to be like. It shaped self identity and it shaped peoples’ perceptions.”

Oglala Sioux artist Joe Pulliam smudges to clear bad energy at the former Arrowhead Inn liquor store in South Dakota, while helping to prepare it to house Whiteclay Makerspace, a communal art and retail space. (Whiteclay Makerspace)

Oglala Sioux artist Joe Pulliam smudges to clear bad energy at the former Arrowhead Inn liquor store in South Dakota, while helping to prepare it to house Whiteclay Makerspace, a communal art and retail space. (Whiteclay Makerspace)

The dehumanizing drain on the reservation haunted ledger artist Joe Pulliam throughout his life.

“Forty or 50 of my relatives were living addicted on the streets of Whiteclay. It didn't matter if it was winter or not. They were severely addicted. Over the years, I've been part of protests and efforts to close Whiteclay. But I was a user then, I was an alcoholic for 25 years,” Pulliam said. “One of my uncles was found murdered in Whiteclay in 1998. Not only murdered but bludgeoned. It wasn't only him but it was hundreds of people that were found dead. We wanted this place closed for years.”

In 2017, thanks to the efforts and activism of Pulliam and many other concerned community members both on Pine Ridge and in Nebraska, the Nebraska Liquor Commission stopped renewing the parasitic liquor stores’ licenses.

Since then, nonprofit Whiteclay Makerspace has opened its doors to help bring the infamous town out of the black hole it once found itself in, and transform it into a place of life-affirming art and empowering economic development.

One of the town’s former liquor stores, the Arrowhead Inn, now serves as the home of Whiteclay Makerspace, a 3,650 square-foot communal and retail space where artists work at stations in the back, while their art is sold in the front. All the supplies and equipment, from quilting machines to Dremel tools, are provided by the nonprofit, and artists are charged $1 a month to rent workspaces.

Nebraska resident, attorney, educator and businessman John Ruybalid (Tewa) started the nonprofit with the guidance and input of Pine Ridge artists, and with grants from the Rapid City Rushmore Rotary and U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“We’re basically trying to provide jobs and provide a place for artists to help themselves. It’s really set up for them to be successful, but they have to do the work,” Ruybalid said. “People will be able to come in and buy art and meet the artists. We will have a trading post supply store there so the artists themselves or others can buy beads, cloth for quilting, leather.”

Makerspace will also provide business training from Native instructors with First Peoples Fund, a nonprofit supporting Indigenous art and culture, and art classes taught by local talent.

Pulliam would relish the chance to pass on his specialty to a new generation.

Ledger art by Oglala Sioux artist Joe Pulliam.

Ledger art by Oglala Sioux artist Joe Pulliam.

“I've gone to college for art and I know the principles and elements of design,” he said. “I want to teach ledger art to kids. A lot of them have given up because they've got alcoholic parents and generations of alcoholism and violence.”

Makerspace is open and has already hosted a handful of small sales. It’s open on weekends and the attention keeps growing, but Ruybalid said it won’t be able to reach its potential until the Covid-19 pandemic passes.

Oglala Sioux Elder and artist Wilma Thin Elk at work inside Whiteclay Makerspace, a communal work and retail space for Native artists. (Whiteclay Makerspace)In the meantime, artists are already benefiting from selling art through Makerspace’s online store. It features a growing gallery of pieces from Pine Ridge artists like Wilma Thin Elk’s porcupine quill bracelets, Sara Fills The Pipe Bass’ beaded dreamcatchers, Brenda Good Lance’s abalone turtle earrings, and Pulliam’s ledger art.

Oglala Sioux Elder and artist Wilma Thin Elk at work inside Whiteclay Makerspace, a communal work and retail space for Native artists. (Whiteclay Makerspace)In the meantime, artists are already benefiting from selling art through Makerspace’s online store. It features a growing gallery of pieces from Pine Ridge artists like Wilma Thin Elk’s porcupine quill bracelets, Sara Fills The Pipe Bass’ beaded dreamcatchers, Brenda Good Lance’s abalone turtle earrings, and Pulliam’s ledger art.

Sen. Foster is a huge Pulliam fan, and she is thrilled that he and other artists have an online platform, which the majority of them lacked prior to Makerspace.

“I can modestly afford Joe’s artwork now, but I shouldn’t be able to afford that level of quality and craftsmanship,” she said. “He holds a lot of knowledge and wisdom and it's expressed in his art. He documents a lot of contemporary things with his ledger art and is very vocal and critical of exploitive systems. He is one of the best kept secrets right now.

According to Ruybalid, the artists set their own prices, and 12 percent of each online sale goes back into the nonprofit.

Pulliam, who has sold several pieces through the online store, was part of the crew that cleaned up the old liquor store last year to prepare for its revitalization through Makerspace. When he returned to the scene of so much loss and sorrow, he felt assaulted by bad energy.

“Before I went into the building I performed my own ceremony,” Pulliam said. “I smudged and I said a prayer out loud and I commanded those spirits and said we didn't want them there anymore, that we were going to uplift people from this place.”

From blight to light

When Pine Ridge artist Norma Blacksmith was 12, her mother started teaching her to sew star quilts. At the time, the young artist was spared from the curse of Whiteclay.

“My parents didn't drink so we never went to Whiteclay,” recalled Blacksmith, who is lending her years of art and business experience to the Makerspace project as a teacher and advisor. “I don't think I really saw it until I was a young adult. It was terrible.”

Blacksmith, now 79, eventually became all too familiar with the town. “I married a man that drank and that's where he used to hang out, so I used to go find him there and bring him home,” she said. “After I got divorced I started drinking and I became an alcoholic.”

More than four decades ago, Blacksmith became a born-again Christian and gave up drinking. Sober and revived, she became an intercessor and activist, focusing her prayers on the redemption of Whiteclay.

“Me and other intercessors prayed for years before the transformation came,” Blacksmith said. “We thought God answered our prayers.”

Whiteclay’s renaissance and the opportunities offered by Makerspace are giving Blacksmith faith in the future of the reservation and its creative community.

“This is what they need,” she said. “They need encouragement and they need a place to go. I’m really excited for them.”

Makerspace artist Sara Fills The Pipe-Bass was never sucked into the Whiteclay vortex. “I stayed away from Whiteclay,” she said. “Since the beer joints all closed down it's becoming a good place to be.”

It will still be a while until Sara can regularly go to Makerspace to create. While she waits, she and her family of artists are getting down to serious business, and have produced enough pieces to fill a small boutique. The nearly thirty options they have for sale online display an astonishing breadth of skill, style and cultural consciousness. Items include elk bone bracelets, a feathered and fringed war bonnet with faux fur, and a pair of beaded black and red dress earrings raising awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

As the Makerspace project falls into place, someone has to keep a handle on all the moving parts.

As of now, Ruybalid has hired one permanent Makerspace employee. Supervisor Candi Red Cloud is playing multiple roles to make the artist space work. “I’m kind of like John’s legs on the ground because he lives in Nebraska and I live on the reservation,” she said.

Consulting and planning with reservation artists and serving as a PR rep are among Red Cloud’s current responsibilities. She’s optimistic about what Makerspace and a reimagined Whiteclay will mean for her people.

“It’s awesome because it will provide jobs, and it looks like some other businesses will move in there,” she said. “We have a Dollar Store there, we have Abe’s New & Used. It's only two miles from the reservation, so we don't have to travel too far.”

It’s highly likely another art-oriented business will soon spring up, as the nonprofit continually fundraises, and enough has been collected to purchase and repurpose another of the old liquor stores.

Witnessing and taking part in the transformation is powerful for Red Cloud, who was a victim of Whiteclay in her former life.

“I was a drinker at one time so I did my share of Whiteclay. I used to hang out over there by myself. It was a very oppressive place. People were dying. There were a lot of car wrecks on the road,” she said. “When they shut down the place and there was no more alcohol it was a blessing. Something good’s gonna happen in Whiteclay.”

Ledger art by artist Joe Pulliam.

Ledger art by artist Joe Pulliam.

Making his way

With the pandemic cutting off a lot of access to art and craft consumers, Makerspace couldn’t have come at a better time for Pine Ridge’s creative talent.

“Right now our artists are probably being hit the most because they are independent contractors, we’re not getting tourism dollars, and they’re suffering. There is an immediate struggle. How can we amplify our artists?” Sen. Foster said. “We’re in a really interesting time in our history and our artists help shape that and carry it. One of our traditional economies is our art, and being able to support that is amazing and empowering.”

Pulliam is well-versed in the reservation’s art world.

“Eighty percent of Pine Ridge residents rely on artwork, bead work, quill work or making quilts, so there's a large population of creative people,” Pulliam said. “We need an economy on the Rez and that economy really is art.”

Before Ruybalid officially stepped in with the nonprofit, Pulliam was already brainstorming and sharing ideas about forming some kind of communal artists’ studio. The two finally met and discussed the possibilities when Ruybalid interviewed Pulliam and more artist activists about two years ago at Camp Whiteclay Justice.

The Camp, formed in June 2017, was one of Pulliam’s grand gestures to wipe Whiteclay clean of alcohol. He was inspired to establish it after his eye-opening experience as an organizer at Standing Rock

“I had come back with a revitalization of my spirit, a rebirth of my Lakota identity, and I decided to make a camp. It was on the reservation right outside of Whiteclay. We were a protest camp at first and then we turned into a prayer camp,” he said. “We had five or six teepees and we had a little kitchen tent there and people would come and just tell us the stories of their loved ones that were dead, that were dying of alcoholism and that had passed away. We just started this big awareness campaign.”

The liquor store licenses had already been revoked by the time Camp Whiteclay Justice was formed. Pulliam said there was still more work to be done because alcohol use still hadn’t been banned in Whiteclay, and problems persisted despite the store closings.

“We wanted the Nebraska Liquor Control Commission to outlaw alcohol there permanently,” Pulliam said. “There were street people living in Whiteclay still drinking and still hoping the stores would open back up. They were getting their alcohol from Rushville, which was 20 miles away.”

In September 2017, the commission finally outlawed alcohol in Whiteclay.

“The credit goes to thousands of people through the years that were trying to bring awareness,” Pulliam said.

These events unfolded during a very challenging transition for Pulliam, who gave up alcohol a couple months after returning from Standing Rock — just as the liquor stores were closing.

“It was one of the hardest times of my life. My family pretty much told me they didn't want me to die. I had lost three brothers to alcohol and many family members,” Pulliam recalled. “On my ride home from my daily trip to Whiteclay it just all hit me. I'd usually drink a beer by the time I got back to Pine Ridge. At this moment, though, I grabbed my beer and I was about to open it (despite) all the things that my family was telling me and my better judgment.”

That revelatory moment didn’t result in Pulliam’s ultimate decision to quit drinking, but it was a turning point.

“I cracked that beer and I sat there, and before I drank it I cried. I told myself I have to change my life or I'll be dead within a year,” Pulliam said. “I still drank that beer, but the next day I decided that was it. I realized I can't be saying, ‘I'll do it tomorrow,” and I knew I had to do it. I've been sober three years and five months.”

With his addiction behind him, and a better version of Whiteclay in front of him, Pulliam is plunging headfirst into his art and tending to the creative well-being of the Pine Ridge community through his own efforts and involvement in Makerspace.

“It's a complete turnaround. This is a chance to empower people from that building instead of destroying them,” he said. “I’m hopeful that the Makerspace will help people empower themselves through sobriety.”

More Stories Like This

Native American Designers You Should Know, Part 01Cherokee Nation Showcases Growing Film Slate with Fall Premieres of Incentive-Supported Titles

Chickasaw Artists Represent at Southwestern Association for Indian Arts in Santa Fe

Zuni Partners Share Community-Led Delapna:we Project at ATALM 2025 Conference

Celebrating 50 Years: The Rockwell Museum Looks to the Future with "Native Now"

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher