- Details

- By Michael Meuers

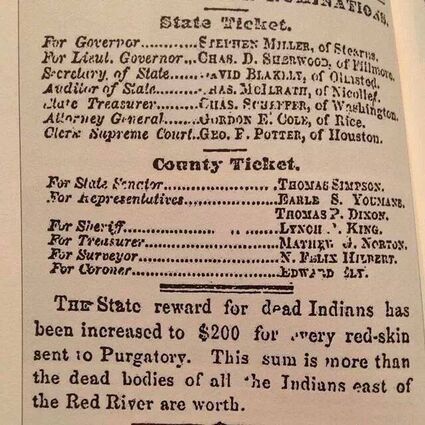

OPINION. The global war on terror isn't ending, nor was it as long as the American Indian Wars. I take issue with the characterization that the war in Afghanistan is America's longest war. America's real longest war was the conflict against Indigenous Americans, called the American Indian Wars, which most historians characterize as beginning in 1609 and ending in 1924 or 313 years, mainly over land control.

The colonization of America by English, French, Spanish, Dutch, and Swedish was resisted by some Indian tribes and assisted by other tribes.

But European settlers came in conflict with First Nation people from the moment they set foot on the shores of North America. From Columbus in the Caribbean to the conquistadors in Central and South America, European nations and First Nation tribes were at odds from the very beginning. From 1492 to 1924 equals 432 years of conflict.

[NOTE: This article was originally published by Red Lake Nation News. Used with permission. All rights reserved.]

The newly declared United States of America wasted no time in antagonizing the native population. They came into immediate conflict with the natives starting as early as 1775.

The American Indian Wars are the United States' most protracted conflict to date stretching from 1775, at the beginning of the American Revolution, all the way until 1924. These conflicts occurred alongside and during all of America's largest wars, including the Revolution, the War of 1812, the Civil War, and World War I. The conflicts lasted a year shy of 150 years and were almost constant for most of the 19th century. These wars are still the most understudied and underappreciated period of American history.

Pick your starting date, no matter.

Some might be surprised to learn one of the last battles twixt US soldiers and Indigenous Peoples took place right here in Northern Minnesota known as the Battle of Sugar Point on the Leech Lake Reservation on January 9, 1918. The Apache Wars ended in 1924 and brought the American Indian Wars to a close.

The number of Indians dropped from an estimated 10 million, (just in what is now the US) to below half a million in the 19th century because of infectious diseases, conflict with Europeans, wars between tribes, assimilation, migration to Canada and Mexico, and declining birth rates.

In 1871, Congress ended formal treaty-making with Indians, obliterating a nearly 100-year-old diplomatic tradition in which the United States recognized tribes as nations.

Although Congress agreed to honor the approximately 368 Indian treaties that had been ratified from 1778 to 1868, Congress stated unequivocally that "henceforth, no Indian nation or tribe . . . shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty...."

Legal historians have tended to downplay the significance of the 1871 treaty-making prohibition, arguing that prior Indian treaties remained in force, that the treaty-making system was merely replaced by bilateral agreements approved by both houses of Congress, and that the independent political status of tribal nations remained largely unimpaired.

Michael Meuers is the editor of Red Lake Nation News.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher