- Details

- By Andrew Kennard

State, national, and tribal politicians and members from at least 15 tribal nations from the Pacific Northwest gathered on July 7-8 in support of decisive action to restore the salmon and orca populations in the region. This Salmon and Orca Summit was co-hosted by the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians (ATNI) and the Nez Perce Tribe on traditional homelands of the Squaxin Island Tribe in Washington.

“We are all salmon people. But unfortunately, we are all also united by the fact that we’re not fishing anymore,” Suquamish Tribe Chairman and ATNI President Leonard Forsman said in remarks at the summit, according to the Nez Perce tribe. “We’re all in this together; this is really about the preservation of salmon people. We have no time to wait. Now is the time to create the groundswell necessary to protect our salmon, our orca, and our people.”

In late May, over 50 of the 57 tribal nations represented by the ATNI passed a resolution in support of Rep. Mike Simpson’s (R-Idaho) Columbia Basin Initiative, according to the Nez Perce Tribe. The ATNI resolution called on President Joe Biden and Congress to fund and implement Simpson’s legislative concept, including the breaching of four hydroelectric dams on the lower Snake River between the summer of 2030 and fall of 2031. The National Congress of American Indians issued a similar resolution in late June.

“Running out of options”

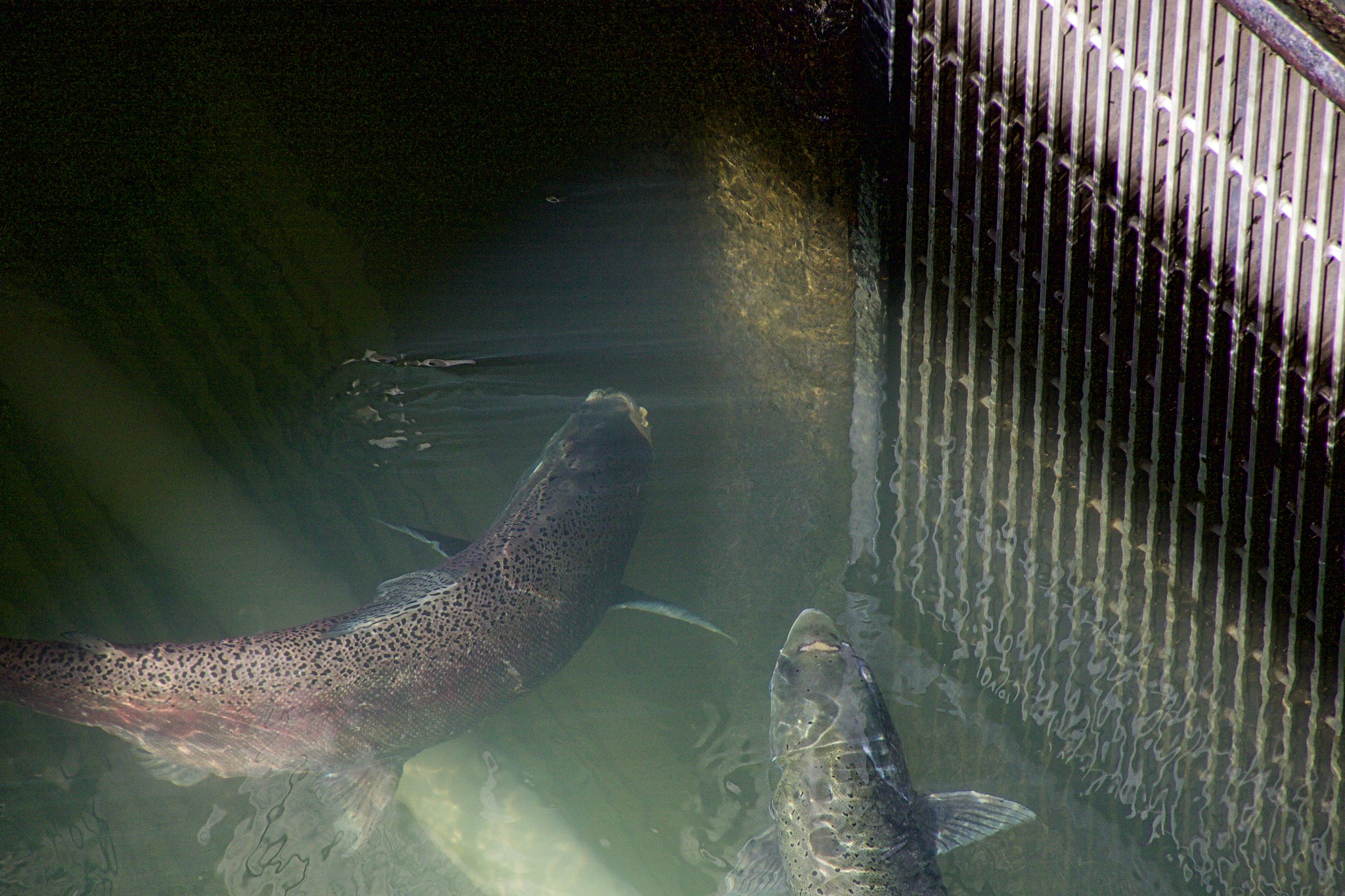

The ATNI resolution recognizes a “very real and imminent salmon extinction crisis” of Chinook salmon, whose migration patterns are hindered by the dams, as well as the decline of starving orca populations that prey on migratory fish. The conservation organization American Rivers emphasized that salmon are “teetering on the brink of extinction” when it found the Snake River to be the most endangered river in America in 2021.

David Johnson, manager of the Nez Perce Department of Fisheries Resources Management, presented data highlighting the plight of the salmon at the summit.

Johnson said that 42 percent of the Snake Basin Chinook salmon have dipped below the Quasi Extinction Threshold. In this case, this biological standard means that there have been fewer than 50 spawners at the salmon spawning grounds for four consecutive years.

“What it really means is that you’re running out of options. When you have fewer than 50 fish on the spawning grounds, your genetic diversity is really limited,” Johnson said. “Your ability to pull these fish out of inbreeding depression or other stochastic-type risks is really limited… There just aren’t enough fish on the spawning grounds to save that particular population. Any type of an environmental hazard can really cause havoc when you have fish populations that are so low.”

Citing the Fish Passage Center 2020 Comparative Survival Study, Simpson’s Columbia Basin Initiative concept says that salmon populations on the Yakima River, which migrate across 4 dams, have enough juvenile salmon returning to spawn in freshwater areas to sustain their populations. In contrast, Simpson’s concept says that the Snake River salmon must traverse 8 dams in total to reach the ocean and have declining return rates that threaten extinction.

“The 4 LSRDs (Lower Snake River Dams) appear to be 4 dams too many for Idaho salmon to negotiate as they make their 900-mile trek to central Idaho,” the Columbia Basin Initiative states.

In September 2020, the Trump administration put out an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) with its plans for the dams. The EIS included fish passage improvement projects at two of the lower Snake River dams and also found that breaching the dams was not the best overall alternative for the environment. The ATNI heavily criticized the Trump administration’s plans, saying that they were “politicized with election-driven timelines” and used regulations weakened by the administration “to justify flawed conclusions and attempt to lock in inadequate dam operations for the next 15 years.”

“A stronger, more resilient Northwest for all”

The ATNI resolution established that invitations to the summit would be sent to the Biden administration and congressional delegations in the Pacific Northwest “to meet and take timely action” on restoring the region’s salmon and orca populations.

Govs. Jay Inslee of Washington and Kate Brown of Oregon, Sen. Patricia Murray (D-Wash.), Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.), Washington State House Rep. Debra Lakanoff (Tlingit) and Simpson all gave some form of remarks at the summit. Acknowledgements of the need to work on a solution to the salmon’s plight were made, and Blumenauer called the removal of the dams a “bold, but necessary action,” according to the Nez Perce tribe.

Inslee thanked tribes for their efforts against climate change, saying that all work done restoring salmon habitats “will all be for naught if climate change makes these waters so hot that salmon can’t simply survive.” The Washington governor praised Simpson’s efforts on the Columbia Basin Initiative but fell short of fully supporting it, saying that “additional spill and dam breaching remain on the table.”

Inslee also noted several key benefits the dams provide to the region and said he believes the parties involved can get “down to business” and take the next steps on this issue in the months ahead.

“I affirm that any comprehensive approach (to the Columbia and Snake Rivers) must account for several critical factors,” Inslee said. “It has to honor tribal rights. It has to protect, to restore, abundant and harvestable native species. Including, as a food source for orcas. It has to ensure clean, affordable, reliable energy for families and businesses. And it has to guarantee our agricultural products are getting to market, and ensure reliable irrigation supplies for eastern Washington farms.”

The Columbia Basin Initiative, which includes a $33.5 billion implementation fund, addresses the replacement of these services, including the carbon-neutral energy provided by the dams. According to Simpson, turning this initiative into drafted legislation will require the combined efforts of politicians, tribes, and stakeholders in the Northwest. Nez Perce Tribe Vice Chairman Wheeler said the next steps are for these parties to work together on a solution and to take the mission to save the salmon to Washington D.C.

“We are salmon people and we are residents of the Pacific Northwest,” Nisqually Tribe Chairman William Frank III said at the summit, according to the Nez Perce Tribe. “We know we can find a comprehensive solution that will remove dams and build a stronger, more resilient Northwest for all.”

“America made a deal”

In remarks at the conference, Simpson said that the extinction of a species should always be prevented if possible, especially when an impending extinction is the result of human actions. Near the end of the summit, the Nez Perce tribe presented Simpson with a pendleton blanket to put on display in his office.

“But what I’ve learned, and come to understand, is, it’s more than that for you,” Simpson said, addressing Native Americans at the conference. “(You support this) for the same reasons I do—we shouldn’t let them go extinct—but you’re trying to preserve a history, a culture, and a religion.”

Members of the Youth Leadership Council of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) attended the summit, where they presented a letter they wrote to President Biden that requested a virtual meeting. The council has also posted a petition on Change.org calling for the removal of the lower Snake River dams.

“America made a deal and promised that we would be able to fish forever,” Youth Leadership Council member Keyen Singer read from the letter at the summit. “We can’t fish if there aren’t any salmon left.”

Casey Mitchell, treasurer of the Nez Perce Tribe, closed the summit with brief remarks, a prayer and a song. He said he wanted to follow the lead of his ancestors, who thought of their future descendents instead of themselves.

“So I want to have that state of mind, that I’m thinking of our future, so they can say, my ancestors did this for me,” Mitchell said. “This is why I can fish, this is why I can still see the orca. Because my ancestors did this for me.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsNavajo Nation Gaming Enterprise Marks Problem Gambling Awareness Month With $3.4M in Support

Cheyenne River Youth Project to Celebrate Women’s Strength at Barbie-Themed Passion for Fashion on March 14

Celebrating Native American Women

Native Bidaské: The Illusion of Freedom and the Myth of America 250, Leonard Peltier Speaks Out

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher