- Details

- By American Indian College Fund Blog

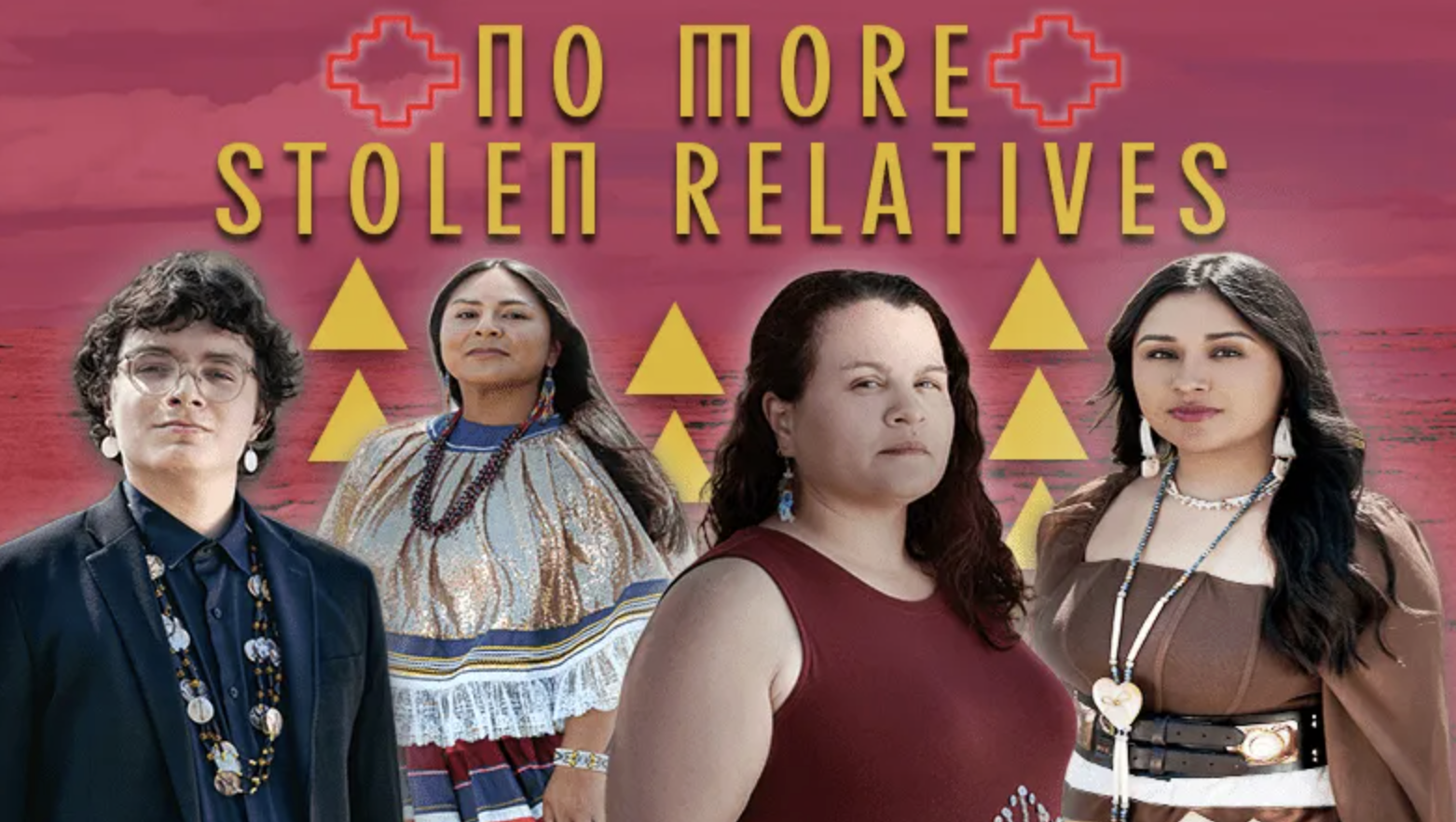

It’s a scene straight from a Dickens novel: a family sits around the table on Christmas Day with an empty chair amongst them and a somber air. Except this isn’t the Victorian classic, it’s real life for far too many Native families and no well-intentioned spirits to save the day. The epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) in the United States that has existed for years continues unabated. And while Native students deal with the same end of semester pressures and holiday stresses as other students, they’re more likely to also be living in a state of fear or mourning for a relative who may never make it home.

A report by the Federal Bureau of Investigations regarding 2024 Missing American Indian (AI) and Alaska Native (AN) Persons Data recorded 10,248 incidents of AI/ANs going missing. A staggering 6,871 of these individuals were juveniles under the age of 18. Per the report, 5,614 of the missing persons were female and 4,626 were male. Those numbers are significant for two reasons: they support the ongoing dialogue of protecting and bringing Native women and girls home but also highlight the fact that all Indigenous individuals are at risk.

The statistics available focus on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), however, who experience violence at greater rates than any other group in the United States. Murder is the third leading cause of death for Indigenous women. The most recent data shows that more than four out of five Indigenous women experienced violence in general and more than half have been abused at the hands of a domestic partner (the vast majority of their attackers are non-Native). Nearly half of Native men have also experienced domestic abuse. Thanks to the history of poor coordination among law enforcement entities and prosecutors to investigate these cases, it is even believed that in addition to domestic violence and sex trafficking there are serial killers specifically choosing to prey upon people in Indian Country because the risk of detection is so much lower.

Please support our year-end campaign. CLICK HERE TO DONATE.

Progress was being made at the federal level regarding awareness of MMIP and efforts to find those missing, seek justice for those harmed, and prevent more people from going missing. Unfortunately, in February of this year, the Trump Administration removed the ‘Not One More’ report which was mandated by the 2020 Not Invisible Act, a critical report addressing MMIP. The decision was both disheartening and came as a surprise, since it contradicted President Trump’s formal recognition of the MMIP issue during his first term in office.

In the absence of federal support, tribal colleges and universities, faculty, and students continue to do what they can to protect and heal their communities.

Navajo Technical University is partnering with the Navajo Nation’s Missing and Murdered Diné Relative Task Force to develop a database that would improve data access, accountability, and coordination around missing persons cases in Navajo Nation. American Indian College Fund Student Ambassador Memory Long Chase (Standing Rock Sioux Tribe) has spent 13 years advocating and providing direct services related to domestic violence, sexual assault, human trafficking, and more in Arizona.

Former Indigenous Visionaries Fellow, Nical Glasses, developed and initiated a community-based project focused on empowering women and creating awareness about safety and MMIW. Another Indigenous Visionaries Fellow, Trinity Moran, spoke candidly about traumatic events affecting her childhood and how she became passionate about MMIP.

Far too many Native students and their families can relate to Trinity’s experiences. In some Native cultures, red is the only color that spirits can see. This is the reason supporters wear red on MMIW Day in March. The REDress Project, an outdoor art installation by artist Jaime Black (Metis), hung empty red dresses in trees as a visual reminder of the women and girls who never made it home.

This is a far cry from the ornaments that so many will hang on their Christmas trees throughout the coming weeks. But our students, communities, and tribal colleges won’t stop working until our relatives are brought home and kept safe. Until then, we’ll be a little blue at Christmas, until there’s no more reason to wear red.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher