- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

SAN DIEGO —On Friday, members of the Kumeyaay Nation and their allies gathered at the Campo Indian Reservation for a second time in recent weeks to stop contractors from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from blasting for border-wall construction right in the middle of Kumeyaay land.

Kumeyaay activist Cynthia Parada, a La Posta Band of Mission Indians councilwoman and founder of the Warriors of Awareness Native American group, was broadcasting live from the protest on Facebook:

“There are supposed to be detonations today, we hope there aren’t, because we found midden soil, we found artifacts and a lot of significant things that make us believe there’s a village site in that area,” she said in the video. “We’re not going to allow them to keep destroying everything. We know what they’re doing is wrong and we’re going to show it to the world.”

Despite the protesters’ efforts, blasting began around 11 a.m., according to Kumeyaay ally Olympia Temiquiani Andrade Beltran, a member of Southern California's Yaqui Nation. Once the blasting started, Beltran announced on her Facebook page that all the protesters were leaving the site with the intention of quickly deciding what to do next.

Parada and the other organizers and leaders are working very hard and diplomatically to be heard and to keep Tribal authorities in the loop, holding Zoom meetings with the Army Corps, making calls to Border Patrol, and debriefing Tribal councils at every step.

One of the protesters’ main demands has been for a Kumeyaay cultural monitor to be onsite throughout the process, in case an artifact is found and work needs to be temporarily halted to remove significant sacred objects.

Kumeyaay leaders and organizers have pleaded for this opportunity since late June. Parada said the Army Corps finally agreed to let a Kumeyaay cultural monitor out to the site on Friday to meet with a project manager before blasting started.

Kumeyaay culture monitors were onsite on Friday, but the meeting with project managers never materialized, Kumeyaay organizer Bobby Wallace (Barona Band of Mission Indians) said on a podcast on Pollen Nation Magazine’s Facebook page following the protest.

“We had the monitors show up and they were having a hard time finding the person they were supposed to meet,” Wallace said. “They couldn’t find these guys.”

The meeting never took place, and the blasting moved forward.

“Somebody needs to be held accountable for this because it’s just flat-out disrespect towards people and our ancestors,” Wallace said. “You know your people have traveled through these hills through time immemorial and they're being dug up and hauled away in trucks.”

Demands and denial

The Kumeyaay have occupied San Diego and northern Baja California for at least 12,000 years. The Nation is divided into twelve bands, including the Barona, Sycuan, Viejas, Campo and La Posta Bands of Mission Indians.

The proposed wall, which is a reconstruction of a steel fence that is already there, is being prepared along the border, about 75 miles east of the city of San Diego. It runs right through the heart of Kumeyaay territory, which extends far beneath the border.

This Southern California standoff hasn’t attracted national attention like The Dakota Access Pipeline, but big political players are starting to take notice.

At the end of June, when the protesters first gathered to stop the blasting, California Senator Kamala Harris, a Democrat, tweeted in support of the Kumeyaay:

“The Kumeyaay shouldn’t have to put their lives at risk during a pandemic in order to prevent the desecration of an ancient burial site. For a pointless border wall. We should all be outraged this is happening at the border right now.”

Soon, Parada and her supporters may get to speak with Sen. Harris and more politicians in person.

Soon, Parada and her supporters may get to speak with Sen. Harris and more politicians in person.

“We’re working on going out to DC and trying to get political attention,” Parada said. “We’re trying to set that up right now.”

The border wall itself is generally unwelcome by the activists, but the Kumeyaay efforts here aren’t so much about terminating its construction as they are about being kept abreast of the project and having an active role in ensuring that no sacred artifacts or remains are damaged.

For two weeks, Parada and the protesters have been demanding that soil testing and cadaver dogs be used to determine what is in and under the site, and that a Kumeyaay cultural monitor be involved.

“We’re just concerned with them doing it without our monitors present to take any bones or artifacts from the area first,” Parada said. “Our cultural monitor has already found artifacts right next to where the explosions were supposed to be.”

Parada said the requests for soil testing and cadaver dogs have been denied. The demand for a Kumeyaay cultural monitor also went up in smoke when the meeting with ACOE project managers planned for Friday never materialized.

In a statement published in the San Diego Tribune, Jeff Stephenson, the supervisory agent for the U.S. Border Patrol’s San Diego sector, said “no biological, cultural, or historical sites were identified within the blasting area located within the Roosevelt Reservation.”

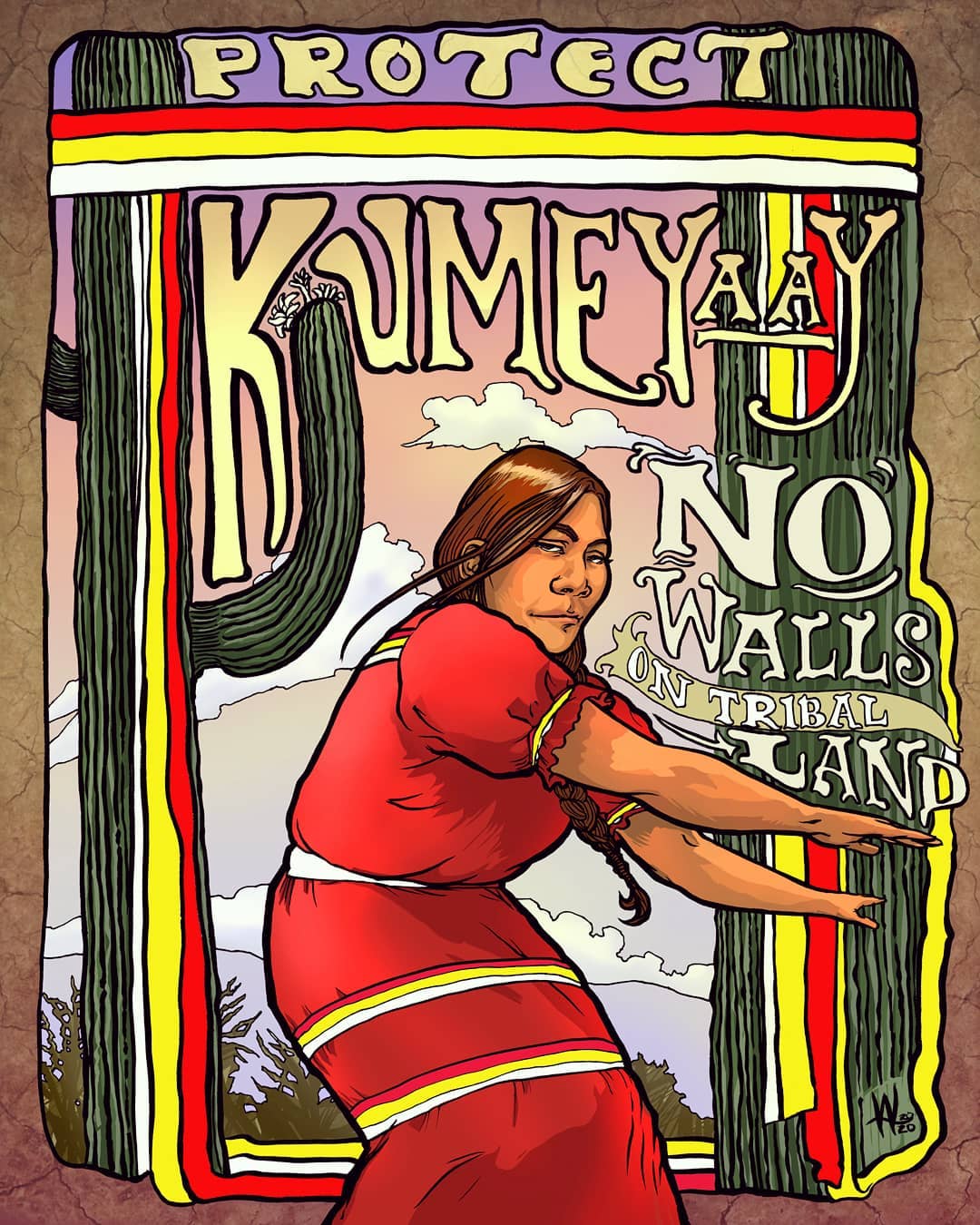

Native American artist Weshoyot Alvitre is a staunch ally of the Kumeyaay, and she created this image to support their struggle at the border wall. California Native issues affect us all,” said Alvitre, who is Tongva. The Tongva are a Southern California tribe located in the Los Angeles Basin and Southern Channel Islands. (Weshoyot Alvitre)The Roosevelt Reservation is not an Indian reservation. Established in 1907 by President Theodore Roosevelt to inhibit smuggling, it’s a 60-foot wide swath of land owned by the federal government that runs for 2,000 miles along the U.S.-Mexico border. Federal and tribal lands make up about a third of the Roosevelt Reservation; private and state-owned lands make up the other two-thirds.

Native American artist Weshoyot Alvitre is a staunch ally of the Kumeyaay, and she created this image to support their struggle at the border wall. California Native issues affect us all,” said Alvitre, who is Tongva. The Tongva are a Southern California tribe located in the Los Angeles Basin and Southern Channel Islands. (Weshoyot Alvitre)The Roosevelt Reservation is not an Indian reservation. Established in 1907 by President Theodore Roosevelt to inhibit smuggling, it’s a 60-foot wide swath of land owned by the federal government that runs for 2,000 miles along the U.S.-Mexico border. Federal and tribal lands make up about a third of the Roosevelt Reservation; private and state-owned lands make up the other two-thirds.

Even though the Army Corps used their own cultural monitor, who claimed there was nothing of sacred value at the site, they really have no idea what is there, Parada said. They’re basing their conclusion on a 10-year-old survey done by the Army Corps with little or no involvement from the Tribe, she said.

Without a warning

Construction contractors working for the Army Corps were supposed to start blasting down the old fence on Monday, June 29. According to Parada, the Kumeyaay community was not alerted.

“We knew it was coming, but they didn’t tell us when it was going to start, and that they were going to have explosions. They didn’t tell us anything,” Parada said. “Anytime there’s supposed to be construction on Kumeyaay land, they’re supposed to notify us and that was never done.”

Despite no warning, some Kumeyaay community members saw what was about to happen and took immediate action.

“On that Monday, we pulled up right on them as they were connecting all the fuses,” said Kumeyaay activist Blue Eagle Vigil (Viejas Band of Mission Indians). “We pulled up right in time and they had to (stop) because there were too many people there..”

For Blue Eagle Vigil, supporting Parada and the cause is a calling.

“We need to protect these lands. We need to navigate this situation,” Blue Eagle Vigil said. ”It’s my duty as a Kumeyaay man to support Cynthia and our Nation, because it’s just something that we do.”

The Kumeyaay and their allies demonstrated solidarity at a peaceful protest in downtown San Diego on Sunday, July 5, by singing traditional songs, brandishing banners, and sharing prayers.

Kumeyaay singers at a peaceful protest on Sunday, July 5, in downtown San Diego. (Photo: Colin H. Richard)“It was exhilarating. It was really good to know that there are a lot of people behind us and they care too,” Parada said. “I believe in unity. It is how we are going to change things. We may be doing this for the Kumeyaay People, but we’re doing it as The People. We’re just the people of the land.”

Kumeyaay singers at a peaceful protest on Sunday, July 5, in downtown San Diego. (Photo: Colin H. Richard)“It was exhilarating. It was really good to know that there are a lot of people behind us and they care too,” Parada said. “I believe in unity. It is how we are going to change things. We may be doing this for the Kumeyaay People, but we’re doing it as The People. We’re just the people of the land.”

The People still have a long way to go.

On the podcast following the protest on Friday, Erica Pinto, Chairwoman of Jamul Indian Village of California (Kumeyaay), said she’s been assured by ACOE that the wall project will go on, no matter what cultural monitors might find at the site.

“It’s expedited and they want this wall done by the end of the year,” Pinto said.

Pinto and the other leaders in the podcast stressed that the Kumeyaay are always more than willing to meet with the opposition and peacefully negotiate. They just want respect, and for the laws that apply to everyone else to apply to them as well.

“When are these government agencies going to learn it is the right thing to consult tribes?” Pinto said. “Now look what it’s erupted into. It could even erupt into a lawsuit.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

Arizona Senators Introduce Bill to Designate Chiricahua as Arizona’s Fourth National Park

Senate Blocks DHS Funding Vote as Shutdown Risk Grows

Deb Haaland Earns Endorsement From End Citizens United

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher