- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

NEW YORK — New York is among the four states that don’t protect all their dead from unintentional excavation—specifically those buried on private lands.

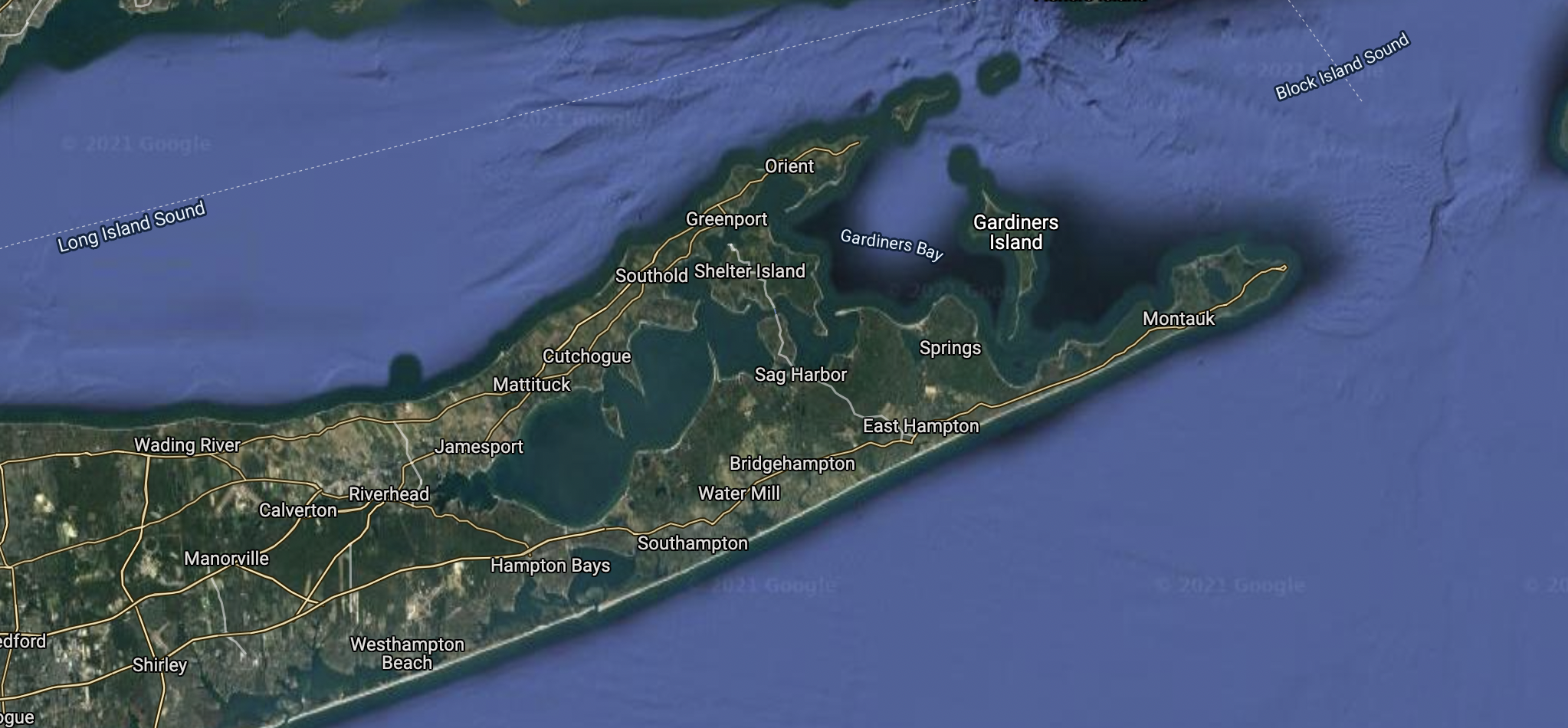

There have been several examples of this over the last two decades, on Long Island, about 100 miles east of New York City. In 2003, a developer on Shelter Island, off the coast of Long Island, unearthed a mass Native burial site on his property, then built a horse barn over the site.

In any other state — except New Jersey, Ohio, and Wyoming— the discovery of an unmarked gravesite would have set off a chain of commands codified by law: from notifying a local coroner who would then call the state archeologist if the remains were more than 50 years old, to establishing a link to a present-day Native American tribe and entrusting the remains to that affiliated group, to criminal penalties for those who don’t comply with the law.

In most places in New York State, property owners don’t even have to call a coroner if they unearth an unmarked grave.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

“New York needs to step up to the plate,” Unkechaug Nation Chief Harry Wallace told Native News Online. The chief, who lives on the Poospatuck Reservation in Mastic, Long Island, is one of the leaders involved in a decades-long effort to pass legislation to protect unmarked graves. “We have been introducing bills since at least 2002,” he said, but all of them have died in committee.

The most recent bill — at least the fifth version pushed by the Inter-Tribal Historic Preservation Task Force primarily composed of roughly half a dozen Algonquian-speaking tribes from the area — was introduced last year by state Sen. John Brooks (D-Nassau County). It would require that construction be stopped on private property if human remains are encountered; create a Native American burial-site review committee; and allow tribes and individuals to seek injunctions against violators.

According to Wallace, the task force includes representation by Cree, Cherokee, Lenape, Matinecock, Mohegan, Matinecock, Montaukett, Pequot, Naragansett Setaukett, Nipmuk, Ojibway, Pequot, Unkechaug, Santee Sioux, Shinnecock, Ramapough Lenape, and Wampanoag.

‘Not enough’

In September 2020, the Town of Southampton, which comprises the village of Southampton and six others on Long Island’s South Fork, finally responded to grave protectors when it declared a six-month moratorium on development in two areas known to have high concentrations of Shinnecock Nation burial sites, and adopted a “protection of unmarked graves” law.

In November 2021, the town passed an additional zoning law that added a third protected area and established a procedure for identifying unmarked human burial sites and culturally sensitive archeological sites prior to certain types of development, “to ensure they remain undisturbed to the maximum extent practicable.”

But Wallace and the Inter-Tribal Historic Preservation Task Force — now called Honor Our Indigenous Ancestors Inc. — say the town law doesn’t do enough.

For one, the new zoning law was developed by the town’s archeologist without consulting the local tribes, tribal members told Native News Online, and doesn’t include the full scope of lands that serve as traditional burial grounds.

‘We know... where our burials are’

There are thousands of unmarked burial sites in New York State, dating from the 1800s through the Indian boarding-school era of the 20th century, according to Shane Weeks of the Shinnecock Nation. He is co-chair of the Graves Protection Warrior Society, an unmarked-grave protection group composed primarily of Shinnecock tribal residents.

In just the last two years, the inter-tribal task force of grave protectors has reclaimed more than 150 human remains that had been unearthed by archeologists and museums in Suffolk County in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“We know as Indigenous peoples where our burials are, but they've never been acknowledged or recognized,” Weeks told Native News Online. “We would like (the town law) to cover areas that we know as burial grounds. We know that there are large areas of places that need studies done before development takes place.”

According to Al Tonetti at the Ohio Archaeological Council, real-estate groups and developers are the main opponents of protecting unmarked graves on private property. He said the state Historic Preservation Office has counted roughly 4,000 locations throughout Ohio where there are mass unmarked Native gravesites, containing “many hundreds of thousands of Native remains.”

“Private-property rights [are] the biggest… thing that's getting in the way,” Tonetti said. “Whether they're Native American or not, [developers] just don't want private-property rights interfered with. Basically… if you own it, you can dig it up.”

A spokesperson for the New York State Historic Preservation Office, Daniel McEneny, told Native News Online that the department “provides recommendations” when human remains are discovered on private property, but there’s no law that requires those discovering the remains to contact any state agency.

McEneny also said the office does not have an estimate on how many unmarked mass graves there are in the state.

‘The timing is better than it's been’

Given the increased national attention to Native American burial sites — both in coverage of museums and institutions returning human remains and artifacts, and the federal Indian Boarding School Initiative announced in June by the Department of the Interior, which will attempt to locate an untold number of unmarked graves associated with Indian boarding schools throughout the country — Wallace said the New York graves-protection bill might have a better chance of passing now.

“The timing is better than it's been,” he said. “I feel that the exposure of these boarding-school burials, but also the thousands of human remains that have been locked in institutions in horrific conditions, are being exposed as violations of archeological sovereignty… the rights of the dead to remain buried.”

When the state Legislature resumes its session in January, the hurdle will be getting the bill out of committee and onto the floor for a vote.

Sen. Brooks is hopeful about its chances, said his spokesperson, Joe Agovino.

“Currently, New York is one of only four states without legal protections for these potentially sacred grounds, and we must make it a priority to preserve these important findings while honoring the cultural ancestry of so many Indigenous people,” Brooks said in a statement to Native News Online. “This legislation places the ability to determine the outcome of these discoveries in the hands of tribal leaders where it belongs, and allows for the greater respect and dignity not only of those who came before us, but for their descendants who live among us today."

If the Brooks bill passes, it would supersede Southampton's graves-protection legislation.

Southampton Town Supervisor Jay Schneiderman told Native News Online that he supports the “long overdue” legislation. “We wouldn’t have had to pass a local law if we had a state law,” he said.

“If we get this law passed through the state, it will compel Southampton to do what it is supposed to do,” Wallace said. “This becomes global in scope. We’re not going to allow our ancestors to be dug up indiscriminately, so New York needs to take action to protect these graves.”

More Stories Like This

Army Seeks Extension in Lawsuit Over Return of Native Childrens’ RemainsDOI places Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation's northern Illinois reservation land into trust

Army to Send Home 11 Native Children from Former Indian Boarding School

Tribal Nations Receive $411,000 to Document Impact of Federal Indian Boarding School Era

Tribes Ask Court to End North Dakota’s Appeal of Native Voting Rights Victories

Native Perspective. Native Voices. Native News.

We launched Native News Online because the mainstream media often overlooks news that is important is Native people. We believe that everyone in Indian Country deserves equal access to news and commentary pertaining to them, their relatives and their communities. That's why the story you’ve just finished was free — and we want to keep it that way, for all readers. We hope you'll consider making a donation to support our efforts so that we can continue publishing more stories that make a difference to Native people, whether they live on or off the reservation. Your donation will help us keep producing quality journalism and elevating Indigenous voices. Any contribution of any amount — big or small — gives us a better, stronger future and allows us to remain a force for change. Donate to Native News Online today and support independent Indigenous-centered journalism. Thank you.